The annual Stoic Week is approaching [1], so it seems like a good time to return to my ongoing exploration of Stoicism as a philosophy of life. I have been practicing Stoicism since 4 October 2014 [2], and so far so good. I have been able to be more mindful about what I do at any particular moment in my day — with consequences ranging from much less time spent on electronic gadgets to more focused sessions at the gym; I have exercised self-control in terms of my eating habits, as well as with my emotional reactions to situations that would have normally been irritating, or even generating anger; and I feel generally better prepared for the day ahead after my morning meditation.

I have also spent some time reading Stoic texts, ancient and modern (indeed, I will probably offer a course on Stoicism “then and now” at City College in the Fall of ’15. Anyone interested?). Which in turn has led to an interest in exploring ways to update Stoicism to modern times not only in terms of its practice (where it’s already doing pretty well), but also its general theory, as far as it is reasonable to do so.

Now, before proceeding down the latter path, a couple of obvious caveats. First off, as a reader of my previous essay on this topic here at Scientia Salon [3] pointedly asked, why bother trying to develop a unified philosophical system? Isn’t life just too complicated for that sort of thing? To which my response is that any person inclined to reflect on his life strives for a (more or less) coherent view of the world, one that makes sense to him and that he can use to make decisions on how to live. One may not label such philosophy explicitly, or even think of it as a “philosophy” at all, but I’m pretty sure the reader in question has views about the nature of reality, the human condition, ethics, and so forth, and that he thinks that these views are not mutually contradictory, or at the least not too stridently so. In other words, he has, over the years, developed a philosophical system. Indeed, I would go so far as saying that even not particularly reflective people navigate life by way of what could be termed their folk philosophical system, whatever it happens to be. Why, then, not try to develop one more explicitly and carefully? And if so, Stoicism happens to be a good starting point, though by far not the only one (I have in the past played with Epicureanism, and also — in the specific realm of moral philosophy — with virtue ethics; other non religious people have adopted secular humanism, of course, or even secularized versions of Buddhism [4]).

Second caveat: beware of changing and re-interpreting things so much that what you are left with has little to do with anything that can reasonably be called Stoicism. This is indeed a danger to keep in mind, but it is often overstated. To begin with, philosophies (and religions!) naturally evolve over time. Even during the classical Stoic period scholars recognized significant differences between the “Old Stoa” of Zeno and Chrysippus (3rd century BCE), the Middle Stoa of Panaetius and Posidonius (2nd and 1st centuries BCE), and the late Stoics of the Roman empire, like Epictetus, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius (1st and 2nd centuries CE). Moreover, no modern philosopher would (or should) adopt the early version of anything his predecessors have proposed, because, you know, philosophy makes progress [5]! That’s why Philippa Foot [6], for instance, was talking about neo-Aristotelian virtue ethics, not the original version by Aristotle himself; or, to take another example, Peter Singer [7] considers himself a utilitarian, but not in the same sense of Jeremy Bentham, or even John Stuart Mill. Similarly, what I’m going after is some kind of neo-Stoicism, inspired by, and as close as possible in spirit to the original, but updated with all the science and philosophy of the many centuries separating us from Marcus Aurelius.

All right, then, let’s get back to work. The inspiration for what follows was provided by a short article on the system of Stoicism by Donald Robertson [8], and more broadly by Pierre Hadot’s The Inner Citadel (cited by Robertson) [9].

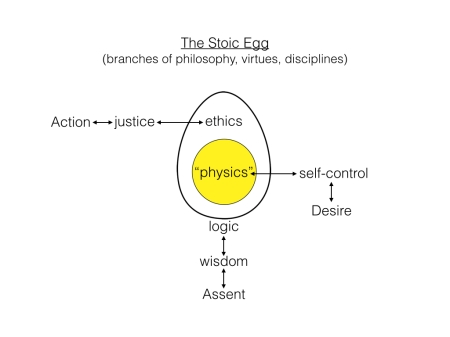

Stoics used a number of metaphors to explain how they thought of philosophical inquiry. My favorite is that of the egg (see figure): the shell corresponds to what the Stoics called “logic,” but which is better understood nowadays as the study of reason broadly construed, to include also a theory of knowledge. The white interior, the albumen of the system, so to speak, is occupied by “ethics”, which for the Stoics, just like for most of the ancient Greek-Romans, meant not just the study of right and wrong, but more broadly knowledge of what kind of life we want to live and society we want to build. The yolk, then, is what Stoics called “physics,” but that in modern parlance really is a combination of all the natural and social sciences, as well as metaphysics. (Henceforth, the term “physics” is the only one I will keep putting in quotation marks, to remind the reader that it refers to something significantly broader than its modern equivalent; I’m happy to keep using ethics and logic without that warning, as the modern meanings of those terms are not too terribly remote from their Stoic sense.)

The Stoics actually disagreed on whether logic or “physics” should be the central topic (apparently, ethics was always in between), but I’ll stick with that view, which also makes the most sense to me. What is the point of the metaphor? To illustrate the idea that the different parts of philosophy (really, what today we would call “scientia”) are interdependent and should not be studied in isolation. If one is concerned with ethics — which many Greek-Roman thinkers thought of as the most important part of philosophy, because it applies directly to human life — one isn’t going to do a good job unless one can reason properly or knows the relevant facts about the universe (physics, metaphysics) and humanity (biology, social sciences). Hence the egg: ethics floats in between the hard shell of logic and the soft core of “physics.”

Before moving to the other components of my little concept map, a few words on beginning to update Stoic logic and “physics.” I will refer the interested reader to the very detailed entry on Stoicism in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [10], but I will also add that I don’t think a neo-Stoic needs to be bounded by the specifics of what the ancients thought about either of these two parts of philosophy, just like a modern Buddhist isn’t bound by everything that has been written in the ancient Buddhist canon (one is, however, bound by Stoic precepts on ethics, which was much more central to their philosophy from the beginning, and became even more so during the Roman period). I say this because there is plenty of evidence that the Stoics themselves modified their views over time in response to criticism from rival schools, particularly the Skeptics, and I don’t see why the process has to arbitrarily stop with the Fall of the Roman Empire.

Still, let’s take a quick look at some of the basic characteristics of Stoic logic and “physics,” and how we can make sense of them. Beginning with logic, then, the Stoic approach was focused on propositions, rather than terms, which made it distinctive from Aristotelian logic, and much more akin to modern propositional logic, particularly the work of Gottlob Frege. Stoics also developed a system of deductive logic, thanks in large part to Chrysippus, that represented an alternative to the Aristotelian approach.

I find it interesting that the Stoics thought that there was a sensible distinction to be made between concrete bodies and abstract entities, while at the same time rejecting the idea of incorporeal beings (which was accepted by Aristotle, and of course later on by the Christians). This is compatible with a modern kind of varied ontology, one that reserves material existence for objects while acknowledging “existence” of some types of things like concepts, mathematical structures, and the like. I myself am pretty happy with this sort of pluralist ontology, being a naturalist more than a strict physicalist.

Within their concept of logic the Stoics included a theory of knowledge, which was based on the idea that reason can — aided by the senses — lead us to at the least approximate truths. They also thought that we are capable of passing judgment on our “impressions” of the world, distinguishing correct ones from incorrect ones. Modern cognitive science has significantly diminished the scope of right judgment that human beings are capable of, but the fundamental idea is that we can reason on whether or not we have formed a correct representation of reality, without which assumption even modern science (including research on cognition) would go out the window. Stoics, in a remarkably modern fashion, acknowledged a continuum of reliability of our judgments, with the highest degree of knowledge achievable only through the use of expertise and the collective effort of humanity [11]. Again, the details are historically interesting, but need not be imported wholesale into any form of neo-Stoicism. What is important, in my mind, is an appreciation for the general spirit of inquiry, the reliance on reason and empirical evidence, and the crucial idea of expert peer judgment, all of which fit rather well with our modern conception of rational and scientific investigation.

What about Stoic “physics” (i.e., natural and social science, as well as metaphysics)? The Stoics were materialists who believed in universal cause and effect, so in that sense their natural philosophy has little difficulty being updated to our modern conceptions of physicalism (or, for me, naturalism) and even determinism (on the latter point things are a bit ambiguous, as some Stoic writings confuse the concept of fate with that of universal cause and effect, they need not be the same).

However, Stoics also believed in Logos, a rational principle underlying the functioning of the universe. Now, they referred to Logos also as Zeus (God) or Nature, which leaves room both for a compatibility between Stoicism and some religious traditions (e.g., Christianity), or an entirely atheistic view of the cosmos [12]. (Incidentally, I find the similarities and compatibilities between Stoicism and other philosophical and religious doctrines, such as both Christianity and Buddhism, an unqualified plus.)

There are two modern interpretations of Logos that can be proposed, one rather uncontroversial, the other more radical. The uncontroversial way of looking at the Stoic Logos with modern eyes is something analogous to Galileo’s famous statement that the book of nature is written in mathematical language: the universe really is structured according to logical principles, which is what makes it (partially) understandable by human beings deploying the tools of reason, science and mathematics. This line of reasoning could even be pushed a bit further, ending up in a claim similar to the idea of ontic structural realism advocated among others by James Ladyman [13]: at bottom, there are no particles or “things,” the fundamental structure of the universe just is mathematical relations. The more radical version of this is that the underlying reason for the logic of the universe is that we live in something like Max Tegmark’s mathematical universe [14], or even inside one of Nick Bostrom’s simulated universes [15]. I’m not going that far myself, preferring instead the solid Galileian ground. Still, it’s fun to think about the other possibilities as well.

And so we come to ethics and the remainder of my concept map. You will notice that the different parts of the egg are connected to three of the fundamental Stoic virtues (justice, self-control, and wisdom [16]), which in turn are linked to the three Stoic disciplines described by Epictetus (Action, Desire, and Assent). Let’s see what that’s all about.

The most obvious and self explanatory connection is between the study of ethics and the virtue of justice. The latter, in turn, is linked to the discipline of Action, which for Epictetus consisted in making sure that we act in accordance with our duties, beginning with those imposed by our natural (i.e., family) and acquired (i.e., friends and other human beings) social relations. And let’s not forget that Stoic ethics included the principle of an expanding circle of concern, which is supposed to extend to all humanity, and even to nature as a whole.

But what is the connection between “physics” (i.e., science broadly construed, to include metaphysics) and self-control? Here, I take it, the idea is that science also teaches us broadly about what is physically possible and impossible and specifically about human nature, and therefore allows us to understand, relate to, and act on human desires. It is this understanding that makes self-control possible, and the discipline of Desire is how we teach ourselves what is good to seek and what is best to avoid, in accordance with human nature and — even more broadly — with humanity’s place within the cosmos. (The latter need not be teleological, as the Stoics did believe it was; it can simply mean an understanding of humanity within the context of a physical universe and its laws.)

Finally, we have the link between logic and the virtue of wisdom, because wisdom comes from rational reflection on our experiences. This, then, is connected to the discipline of Assent, which is the one through which we develop the ability to discriminate what is (likely) true from what is not, or to suspend judgment if we cannot arrive at a reasonable conclusion.

The very fact that the three parts of Stoic philosophy are all connected not just to each other, but to virtues and disciplines underscores once more the idea that for the Stoics it was ethics that was the central concern of philosophy, with other types of inquiry (including science, in modern parlance) needed as aids to develop knowledge of how to live. Which seems a fine concept to me.

Now, the above may not be your cup of tea, of course. But I think it represents at the least the beginning of an attempt to update the whole of Stoic philosophy into a version that is compatible with modern science (and philosophy) and still useful and meaningful for 21st century human beings. This is no different, really, from ongoing attempts at secularizing, say, Buddhism (or even, more controversially, Catholicism), to provide a system of beliefs and practices that can be adopted by people in search of reasonable alternatives to religions but who are turned off by the incipient nihilism [17] of straightforward atheism (especially of the currently popular, strident variety).

As I’ve said for a long while now, there is a rich middle ground between religions and atheism, a middle ground occupied by a number of philosophical systems — including, but not limited to, Secular Humanism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Epicureanism, and of course Stoicism. And as philosophies go, one that says, as Epictetus famously did in the Discourses, “What, then, is to be done? To make the best of what is in our power, and take the rest as it naturally happens,” is most certainly not a bad one.

_____

Massimo Pigliucci is a biologist and philosopher at the City University of New York. His main interests are in the philosophy of science and pseudoscience. He is the editor-in-chief of Scientia Salon, and his latest book (co-edited with Maarten Boudry) is Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem (Chicago Press).

[1] Stoic Week 2014: Everything You Need to Know.

[2] How do I know? Because that’s the date of my first entry in my evening meditation diary, which is one of the regular practices of a Stoic, according to the Stoic Week handbook.

[3] Why not Stoicism?, by M. Pigliucci, Scientia Salon, 6 October 2014.

[4] See, for instance: The Bodhisattva’s Brain: Buddhism Naturalized, by O. Flanagan, 2013.

[5] I have just finished writing a book on this topic, hopefully to be published soon by Chicago Press.

[6] See: Virtues and Vices: And Other Essays in Moral Philosophy, by P. Foot, 1979.

[7] For instance: How Are We to Live? Ethics in an Age of Self-Interest, by P. Singer, 1994.

[8] The System of Stoic Philosophy, by D. Robertson, Stoicism and the Art of Happiness, 18 October 2012.

[9] The Inner Citadel: The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, by P. Hadot, 2002.

[10] Stoicism, by D. Baltzly, SEP.

[11] The “ideal Sage” was supposed to be capable of perfect knowledge. Then again, unlike the case of religions such as Christianity and Buddhism, the Sage was never meant to be thought of as a real person (let alone a God), or even as something a real person could possibly become. It was rather an ideal to constantly strive for.

[12] Incidentally, by “Zeus” the Stoics most certainly didn’t mean that popular image of a lascivious god who kept taking animal form in order to seduce and have sex with a number of unsuspecting (and characterized by rather bizarre sexual tastes!) human females.

[13] James Ladyman on Metaphysics, Rationally Speaking podcast, 8 September 2012.

[14] Max Tegmark on the Mathematical Universe Hypothesis, Rationally Speaking podcast, 8 February 2014.

[15] David Kyle Johnson on the Simulation Argument, Rationally Speaking podcast, 28 April 2012.

[16] The forth cardinal virtue, courage, is often associated with self-control, as to be courageous means to control one’s fears.

[17] Nihilism, Rationally Speaking podcast, 2 November 2014.

“Stoics, in a remarkably modern fashion, acknowledged a continuum of reliability of our judgments, with the highest degree of knowledge achievable only through the use of expertise and the collective effort of humanity .” That is remarkable. I never knew Stoics had had that insight. They could have started their own magazine!

LikeLike

Massimo,

I like your concept map a lot. I’ll be chewing on this for awhile.

“Stoics, in a remarkably modern fashion, acknowledged a continuum of reliability of our judgments, with the highest degree of knowledge achievable only through the use of expertise and the collective effort of humanity”

What Humble said.

LikeLike

Thanks for the excellent essay, Massimo. I am trying to do the same with a secularized form of Buddhism that you are Stoicism. Further, a colleague and I have a paper in publication now arguing from Hadot’s work and others to the thesis that the Buddha of the Pali Canon (Siddhattha Gotama) can be seen as a philosopher in the Western sense. His approach is most like that one finds in the Classical philosophers such as the Stoics and Epicureans, or even Socrates himself. This is not, of course, to say that their philosophical conclusions were identical, however their approach to philosophy as that which illuminated eudaimonia, or the way one ought to live, was broadly coterminous. Further, their didactic approach was similar, involving dialogues and piecemeal arguments rather than any sort of systematic theoretical approach.

While one can find mention of issues regarding physics and logic in Gotama’s work, any comparison with modern fields cannot be anything more than cursory. Gotama’s main interest in physics per se involved the awareness that all things were causally conditioned and hence impermanent. Although he did make reference to the four elements and their interrelations, the specifics of such an account lay outside of his area of interest.

Gotama was more interested in the ‘psychophysics’ (if you will) of desire and clinging, how it is formed through certain kinds of experiences, and how it could be dissolved. In that sense, he did not consider physics and logic to be a central part of eudaimonia, except insofar as it was directly useful to illuminating ethical issues.

Early Buddhist ethics are broadly similar to those you sketch above. Although his was in the main a monastic enterprise, and thus one’s duties were most specifically seen as centered around the sangha of fellow monastics, Gotama did actually have quite a bit to say about ethics in lay life, and about one’s duties to parents, which he viewed as important. In particular for laypersons, one was to pursue ‘right livelihood’, which among other things meant living within one’s means, and avoiding engaging in any business that harms living things such as selling weapons, slaves, poisons, and so on.

While Gotama did not subscribe to any principle of logos or, as you put it, “rational principle underlying the functioning of the universe”, one can see similarities in the Greek notion of Cosmos and the Buddhist conception of dhamma. The problem for translators is that this term has many, varied meanings. One of them however is more or less “the way things are”; this “way” more than anything involves constant change due to unending causal conditioning between “dhammas” or elements of reality. His so-called formula of dependent arising, a causal pattern he saw repeated within and between human lifetimes, can perhaps be seen as a kind of logical abstractum. Thus it is somewhat akin to your “Galilean” sense of the term “logos”. It does not support any theistic or triumphalist view of history, however. The early Buddhist view of history was firmly cyclical.

One final point about secular Buddhism: although I enjoyed Flanagan’s book on naturalizing the Bodhisattva, Flanagan appears not to fully embrace the task. Further, he conflates many, quite different schools of Buddhist thought into one monolithic “Buddhism”, which does not do justice to the historical tradition. As modernists of course it is up to us to pick and choose what we like; the mere fact that one thing lies in one tradition and another in another isn’t of any problem in principle. However by approaching the problem as he did, I believe Flanagan missed many nuances that are actually more helpful to a secular approach, and which as I’ve said can be found in the earliest, Pali traditions.

I’ve written about this a bit over at the Secular Buddhism site, for example comparing Secular Humanism to Secular Buddhism. The main difference, one which it shares with your Stoic approach, is that Secular Buddhism is a path to practice rather than simply being a system of beliefs.

http://secularbuddhism.org/2012/11/29/secular-humanism-and-secular-buddhism/

LikeLike

I really appreciate the coverage of stoicism. I never looked into stoicism too seriously but it always had an appeal to it, similar to a lot of the other traditions you mentioned (buddhism). However, I often find myself torn between modern psychological approaches to living a good life (many of which mirror stoic practices) and the contemplative traditions of the past. I think these traditions have a lot to offer and we could modify them but they don’t seem drill down far enough to gain a newer understanding of why their methods work and how we can improve them.

In that sense, I like to look at the contemplative traditions as a possible source of good practices but when it comes to putting it together for myself or for my research, I prefer to take the more science oriented route. I see this as somewhat similar to the process that medicine went through, where traditional practices that worked were refined by biomedical research into modern medicine, while leaving behind the methods that were not effective.

The other side of this coin is that most psychological approaches are far from being comprehensive, with many focused on pathology or self-help style “be happy” programs. Moreover, outside of existentialist programs, I have yet to find a psychological program that provides a robust coverage of philosophy. Most programs simply have clients pick whatever goals they want and go with them, without much philosophical exploration of what the right way to live is.

LikeLike

Dear Massimo, Science is the act of measuring and dividing a Universe truly immeasurable and indivisible, and now you come to philosophy and try to do the same with it. Truth is indivisible, don’t you know.

Measure and division is a hard habit to break. It is even worse than cigarettes. And there are no warning labels yet on our rulers. So far to go, so little time, aaah, MEASURE! If I may, to break the habit try to measure the depth and flow of a river. the truth may set you free. =

LikeLike

I would say that Stoic “physics” also encompasses modern social psychology, which can be applied in Stoic practice to diffuse anger toward others. For instance, anger often arises through an insistence of a “tyrannical should” – that a person should not behave in a certain way, partially through a sloppy projection of one’s own life into that other person’s shoes. But given that there’s causal conditions which lead that person to be that way, one is essentially wishing that the conditions of the universe to be other than they were, and for that wish to magically come true! By realizing that another person’s behavior is influenced by their environment, and that there exist causal reasons for that behavior, one can de-personalize the anger and remove blame from that person, and instead focus on ways to help that person through the causal leavers of the universe (if possible) instead of merely dwelling in anger.

LikeLike

Hi Massimo, apologies if somebody has already asked you this: I am just wondering whether you have read Tom Wolfe’s “A Man in Full”, and what you think of it.

LikeLike

A few thoughts

Massimo without being too details (and I don’t think you have to be), what do you see as major differences and transitions between early, middle and late Stoicism? One part of the transition from middle to late Stoicism, in my mind, is the move from republic to empire in Rome, and perhaps a bit more fatalism or similar. Perhaps also a bit less metaphysical stance? And, it does seem that late Stoicism started to overlap somewhat with Cynicism as it revived in the Empire, although Julian, among others, worked to revive and separate it.

On the Logos, I’ll modernize it less than that. And, while it is true that inanimate matter does indeed operate by various natural laws, at least on the one planet that we know to be populated by sentient beings, the sentient beings show little tendency to operate in such rational fashion.

Here I reference Camus, saying he did “not believe sufficiently in reason to believe in a system.”

One can counterargue that this is an is-ought issue. But the counter-counterargument would be that an “is” of conscious/slow thinking is a lot easier to change than an “is” of unconscious/fast thinking.

Second, I agree on the middle ground. That said, with a modern developed world seemingly becoming more and more “disconnected” in some ways, and a world population looking like it will still hit 9 billion before the end of the century, and with mass marketers in the developed world pushing various forms of capitalistic-connected conformity, I think you need to add Cynicism to the list. Actually, not so much “you” as I think society needs a neo-Cynicism. It would probably need different focal points in some ways than the ancient version, and more “denaturing” along with that.

That said, I see Cynicism as having some influence on Sufi Islam as well as certain strains of Christian denialism like the “holy fool.”

Without doing everything Diogenes did, maybe we could call neo-Stoicism “the stiff upper lip” and Cynicism “the laughing sneer.” Or, per Camus, who I argue has some direct intellectual connection with the Cynics, to live it — at least inwardly — as a rebel.

And, I guess that’s part of my discomfort with ancient Stoicism, and one that’s referenced a bit by a few other philosophers I’ve seen writing about Stoic Week — its comfort with the powers that be, and situations that may be.

Taking off on the Serenity Prayer, I would rather do and speak differently.

Rather than “accepting the things I cannot change,” instead, I would “accept there are things that I cannot change.” The SP/Stoicism idea would have us ignore the emotions attached to those unchangeable things, and it would have us also ignore that these things often exist for very irrational reasons.

That said, I find it interesting that the Stanford Enclyclopedia of Philosophy doesn’t even have an entry for Cynicism.

And, yes, I’m kicking around writing about neo-Cynicism as my next submission here.

LikeLike

What about Benedict Spinoza’s update of Stoicism? Not modern enough?

Regarding the objection to teleology–how is determinism (which is compatible with modern science) different then teleology?

Marcus Aurelius said: “Whatever may happen to you, it was prepared for you from all eternity; and the implication of causes was from eternity spinning the thread of your being, and of that which is incident to it.”

This teleology does not require an anthropomorphic super consciousness which sets up the conditions which ‘spins the thread of our being’. It just means that what is was always going to be; that the implication of causes are not something different then the affects we experience. So, we can even keep the notion that consciousness is a necessary component of teleology because we are conscious and we have purpose. Furthermore as individuals, as an evolving species, and an evolving civilization, we give purposeful function to a material world that would otherwise presumably function without purpose. But this ‘otherwise’ does not exist, because our being was spun into the universe from eternity; in a deterministic universe it couldn’t have been otherwise.

LikeLike

Douglass,

“In that sense, he did not consider physics and logic to be a central part of eudaimonia, except insofar as it was directly useful to illuminating ethical issues.”

Something like that, as I wrote, holds for the Stoics as well. Though theirs is a “complete” philosophical system, it is clear to me that they meant the “logic” and “physics” parts to be in the service of the ethics component. And, frankly, the more time passes the more I am sympathetic to that sort of approach.

“The early Buddhist view of history was firmly cyclical”

Interesting you mention this. I neglected that aspect in my essay, but so was the Stoic view: the universe begins in a great fire, ends the same way, and then it starts over.

“comparing Secular Humanism to Secular Buddhism. The main difference, one which it shares with your Stoic approach, is that Secular Buddhism is a path to practice rather than simply being a system of beliefs.”

Indeed, which is one of the reasons I’ve been attracted to Stoicism lately. Secular humanism has increasingly felt a bit too theoretical (and, at times, a bit vague) to be useful.

imzasirf,

“I like to look at the contemplative traditions as a possible source of good practices but when it comes to putting it together for myself or for my research, I prefer to take the more science oriented rout”

The way I distinguish the two is by thinking of Stoicism as a philosophy — hence a matter of personal choice — and of cognitive behavioral therapy and the like as science. The two are certainly compatible and complementary, but luckily at this moment of my life I need a philosophy, not therapy!

“The other side of this coin is that most psychological approaches are far from being comprehensive, with many focused on pathology or self-help style “be happy” programs”

Precisely.

Gregory,

“I would say that Stoic “physics” also encompasses modern social psychology, which can be applied in Stoic practice to diffuse anger toward others.”

Indeed, as I said, “physics” really includes natural as well as social sciences (and metaphysics, which the Stoics — unlike most moderns — rightly saw as tightly linked).

“By realizing that another person’s behavior is influenced by their environment, and that there exist causal reasons for that behavior, one can de-personalize the anger and remove blame from that person”

Seneca (“On Anger”) and other Stoics counseled never to blame or belittle others. At most others lack proper ethical knowledge, for which they need help, not condemnation.

Bill,

“I am just wondering whether you have read Tom Wolfe’s “A Man in Full”, and what you think of it.”

No, I haven’t. I know one of the main characters discovers Stoicism, but have not read the book. Is it worth it?

Socratic,

“what do you see as major differences and transitions between early, middle and late Stoicism?”

Definitely a (further) move toward the centrality of ethics and practice, as opposed to theory. The middle and late Stoics, however, also modified their theory of knowledge a bit, largely in response to criticism from the Skeptics. The Cynics had a huge influence on the early Stoa, Zeno — the founder of Stoicism — was a student of one of the great Cynics, Crates of Thebes.

“Here I reference Camus, saying he did “not believe sufficiently in reason to believe in a system.””

Right, except that I don’t believe Camus or anyone else in this respect. I’ve come to believe that we all have “a system,” except that in most people it is intuitive and not spelled out. Few people openly embrace notions that they understand to be incoherent in their lives, and I’m certainly not inclined to do so.

“I guess that’s part of my discomfort with ancient Stoicism, and one that’s referenced a bit by a few other philosophers I’ve seen writing about Stoic Week — its comfort with the powers that be, and situations that may be.”

I think that’s definitely a misunderstanding of Stoicism, which was very much a philosophy of social involvement and change for the common good.

“Rather than “accepting the things I cannot change,” instead, I would “accept there are things that I cannot change.””

I think the Stoics would agree, remember that the serenity prayer is a Christian thing…

“yes, I’m kicking around writing about neo-Cynicism as my next submission here.”

Looking forward to it!

Burgess,

“What about Benedict Spinoza’s update of Stoicism? Not modern enough?”

Spinoza adopted elements of Stoic ethics, but I’m not aware of any updating in the sense that I am suggesting here.

“how is determinism (which is compatible with modern science) different then teleology?”

Very much, and in fact teleology is incompatible with modern scientific views, which explains the fracas about Thomas Nagel recent book (which was criticizing modern science for lacking a theory of teleology). Teleology, but not determinism, implies a direction of movement, if not a conscious plan.

“This teleology does not require an anthropomorphic super consciousness which sets up the conditions which ‘spins the thread of our being’”

That’s because that sentence by Marcus — like similar ones from other Stoics — can be interpreted both teleologically (which pretty much does require some kind of consciousness) as well as simply commenting on chairs of cause and effect (which doesn’t require any plan).

“we can even keep the notion that consciousness is a necessary component of teleology because we are conscious and we have purpose.”

That’s not the standard understanding of teleology. Our own consciousness and purposes are themselves the results of universal cause-effect.

LikeLike

Socratic,

“discomfort with ancient Stoicism, and one that’s referenced a bit by a few other philosophers I’ve seen writing about Stoic Week — its comfort with the powers that be, and situations that may be.”

I fear you are misinterpreting it.

Seneca: “Surround yourself with philosophy, an impregnable wall; though fortune assault it with her many engines, she cannot breach it. The spirit that abandons external things stands on unassailable ground; it vindicates itself in its fortress; every weapon hurled against it falls short of its mark”

These were times of hardship and great danger. They faced this with iron resolve but that did not mean they were apathetic, far from it. Stoicism is a philosophy of hardiness and resilience, not acceptance and inaction. The resilience enabled them to endure the setbacks and then come back to win.

Publius Scipio Africanus: “We Romans have kept and continue to keep the same spirit irrespective of any changes in our fortunes. Our souls are neither inflated by success nor diminished by failure”

Lucilius: “The Roman people have frequently been defeated by force and overcome in many battles—but they have never lost the war—and that is all that matters”

Livy: “That lot has been given to us by some fate that in all great wars, having been defeated, we prevail”

You may think Seneca’s statement “The spirit that abandons external things stands on unassailable ground” supports your point of view, but that is not the case. The ability to abandon external things enabled them to make the sacrifices that gained them victory.

“the laughing sneer.”

Greatness was never built on cynicism. On the contrary, cynicism is the refuge of failure.

LikeLike

Massimo Thanks for the feedback. First, I agree we all have some system, even if it’s the Tarski-violating stance of being against any system-building!

And, that part is true indeed about Camus.

I may have overstated somewhat, but it still seems to me that, even if Stoicism didn’t like the “powers that be,” whether earthly or cosmic (an issue that a pseudo-Paul adopts in Colossians, primarily), it still doesn’t seem to have the same emotional reaction as Cynicism does, and that acceptance, rather than contempt, is the Stoic approach.

Or, to put it another way — had Julian been a Stoic rather than a Cynic, maybe he wouldn’t have been “the Apostate”?

And, I may have been “back-reading” the Serenity Prayer too much, I’ll admit. This all said, it is interesting to note the overlap between late Stoicism and middle/late Cynicism.

I had known that Zeno studied with Crates; it is interesting how much they diverged, yet started coming back together more around the time of Epictetus and Marcus.

That said, also, even in their time of greatest overlap, I don’t think the Stoics had a developed critique of social convention. I say this in part precisely because, although being some sort of student of Crates, Zeno didn’t follow him into the Cynic path. At the same time, later Cynics, though gaining new influence from Stoics, never really bought into the idea of the Logos in particular or propositional logic in general. That’s not to say they rejected reason in general, of course.

Labnut I may have overstated Stoicism’s resignation, but I don’t think I totally misinterpreted it by any means, and that interpretation is not held by me alone. Indeed, early Christian apologists claimed that they had a better alternative to Stoicism in part by addressing its world-weariness.

On the other hand, you seen to be confusing Cynicism the philosophy — http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cynicism_(philosophy) — with cynicism the psychology. The capital-C philosophy did have a “sneering” take to convention — but that was not the end point of the philosophy by any means. Rather, Cynicism was about a true “callout” of convention and authority, as tools to reach the Cynic understanding of eudaimonia (flourishing). The “sneer,” if you will, was a tool to try to break the non-Cynic’s attachment to convention, be it convention of power, fame, money, or mores. The “sneer” is because Cynics know we can do better.

Indeed, this is why some biblical scholars, like John Crossan, have postulated Jesus as a Jewish cynic. (Middle-era Cynicism was strong in the biblical Decapolis, as well as east Syria.) I think Crossan overstates the case, but it’s not totally implausible at all.

So, no, Cynicism the philosophy is not “the refuge of failure.” Note Massimo above, as well as me here, on its overlap with Stoicism.

Beyond the Wiki link, I highly recommend this book: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/5712253-cynics?ac=1

Per both you and Massimo, some of what is identified with middle Stoicism can also be classified as independent Roman mindset, too. And, my essay is writing, obviously!

LikeLike

Hello again, Massimo. “… holds for the Stoics as well. Though theirs is a “complete” philosophical system, it is clear to me that they meant the “logic” and “physics” parts to be in the service of the ethics component. And, frankly, the more time passes the more I am sympathetic to that sort of approach.”

Yes. Though this does present a potential pitfall, which is in allowing values to taint facts. In Buddhism this comes across (at least nowadays) in an apparent blindness to the ways in which science countenances the *lack* of change among physical things. For example, fundamental particles have very, very long mean lifetimes, and some may indeed be everlasting. You will know better than I about hypothetical interpretations of physics on which the world may perhaps be made up of mathematical abstracta which are not themselves subject to change, or at least not within a universe.

These are all differences that, from the point of view of early Buddhism, really don’t make a difference, so long as one takes the claim of “seeing the way things really are” with a grain of salt. The large, compound items we find in daily life really do change all the time, and really are not permanent. “Seeing the way these things are” (that is, the furniture of everyday sense perception) is valuable to living a eudaimonic life. But it also may cohabit with other facts about basic physics or mathematics that say otherwise. Since I do not believe that clinging to mathematical abstracta, or to the arguable immortality of the electron, provides any real psychological solace, I am not inclined to take this as a good argument against a Secular Buddhist practice. Though I think it does bear consideration.

LikeLike

Hi Massimo. Re “A Man in Full”, I wouldn’t exactly call it a great book, but since Stoicism is a major theme, I think you would at least find it interesting.

Best regards, Bill

LikeLike

There is quite a bit I like concerning the Stoic approach as presented in the two essays here at Scientia. I especially like the practicality of the idea that philosophy should ultimately serve ethical being, and play also play an important role in providing practices that serve that end. I also think the traditional Stoic practices where they do not overlap seem to serve as a nice complement to practices that emerged from eastern philosphical systems.

I do think if an updating is proposed however, a good place to start would be with the egg diagram. It is nice that ethics is central, but the diagram leaves no place for physics/desire to interact with logic/wisdom except through ethics/action. I think a model allowing for direct interaction and feedback among all 3 branches allowing for emergence of new progressive factors in the ethical branch might serve as a foundation for update. I obviously haven’t thought this through in any detail, but a structural equation model might be interesting.

LikeLike

Actually, I look forward to SocraticGadfly’s article on stoicism/cynicism and perhaps a lengthier treatment of their overall differences. It has always seemed to me that Socrates, particularly in his rather ironic moments, had more in common with Cynicism than Stoicism. And the ascetic leanings of the Cynics has much more in common with early Christianity than did Stoicism. And, for better or worse, there seems to be a more pronounced element of skepticism in Cynicism. I’m more inclined by personality to favor what seem the eccentricities of particular Cynics than the systematizing of the particular Stoic philosophers.

LikeLike

Massimo,

continuing to follow your development of this thinking with interest.

By the late 1800s, philosophers discussing ethics largely abandoned the question of personal practice in favor of politics and social theory. This was understandable, given the social, political, and cultural changes going on, but it did leave a vacuum. And by the 1970s most American philosophers were no longer interested even in politics. So by the late 1970s, all manner of New Age woo and cultic pseudo-religions (like Scientology) were pouring in to fill the space.

It seems finally that many of us are looking for a rational theory that can not only be deployed politically, but which can also inform how we relate (as individuals) to others, and to ourselves. In an era of increasing irrationality in public discourse, this is ceratinly a good thing, and I think adds both content and contextual significance to the practice of philosophy.

Douglass Smith,

thank you for your clear presentation of the secular Buddhist position here.

Labnut,

SocraticGadfly’s remark on Cynicism specifically refers to Diogenes. It’s important to distinguish the Greek school (for which the major theorist appears to have been Antisthenes) from its later Roman appropriation. It is the nihilistic Roman form of Cynicism that has come down to us and upon which the common usage of the word ‘cynic’ depends. But despite Diogenes’ undeniably extreme behavior, and Antisthenes’ asceticism, the Greek school has much to offer as for a theory of personal ethics, especially insofar as it casts a cold eye on social formalisms that are to some extent illusory.

On the distinction between the Roman school (and its modern implications) and the Greek school (and its possible contemporary uses), Peter Sloterdijk wrote a fairly accessible, well-informed study in 1983, Critique of Cynical Reason (English translation, 1988). It’s been a long time since I’ve read the book, so I can only recommend it tentatively now; but it does explain this necessary historical distinction between the Greek and Roman schools. Although it tends toward the post-modern, it actually helped me resist the temptations of post-modernism. (There’s something intriguingly, refreshingly Zen about Diogenes; but there would seem to be not much fun in self-immolation for-the-hell of it, a recurrent Roman cynical public display, which re-appears today as celebrity self-destruction.)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diogenes_of_Sinope

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antisthenes

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critique_of_Cynical_Reason

LikeLike

As always, ejwinner, insightful commentary. Getting back to SocraticG’s comments, perhaps the following touches on some of his points. If not, I’ll await clarification:

http://systemofthecynics.blogspot.com/2012/09/difference-between-ancient-stoicism-and.html

LikeLike

Massimo, I’m also interested in updating Stoicism, the only other attempt I’ve seen (William B Irvine’s booK) was philosophically light and very unsatisfiying, and some of Ricardo Salles much better work. I play with this updated Stoicism constantly and see it as part of a postnihilist praxis (cf. http://www.syntheticzero.net) , but I am also very wary of it operating as a consolation that limits the field of possible actions too much. That said, I have written on this kind of Stoicism in a similar fashion but from a different perspective. Thus far my most fully worked out attempt to integrate Stoic physics with contemporary ontology is in a blog post I’ll link below- “Towards a corporealism”. In that post I discuss Stoic physics in relation to an ontological realism/naturalism that is coincides with understandings of the self-organisational (or non-hylomorphic) capacity of matter and how this relates to immanence. I do this by paying particular attention to how “God” operates for the Stoics.

Three problems that I think we can’t ignore in approaching the Stoics:

1) Contemporary philosophical accounts of “nature” are more complex than the providential rational system of the Stoics. Here I’m thinking of Timothy Morton, Bruno Latour, others like that.

2) CBT. This is really several problems. a) the evidence base isn’t really that strong and the research design of evidence-based practice is deeply problematic and may spoil the positive evidence. b) CBT has been allied to various noxious socioeconomic and political forces. There are plenty of critiques of CBT out there on both grounds (I’m writing something that brings them together), but the use of philosophers like Epictetus must be able to distance itself from these critiques.

3) Cognitive psychology is an incomplete psychology. The dominant way of appropriating the Stoics are from within cognitive psychology. I am not going to argue that cog psych is wrong (Richard Bentall is among my favourite psychologists and the experimental evidence for heuristics and cognitive biases is impossible to refuse), but I would say it is incomplete and makes some fundamental philosophical assumptions that cognitive science has already begun to seriously slough off. Here I’m thinking of the two directions in which this occurs. a) The strains of eliminativism, whether it be the Churchland’s or RS Bakker’s brilliant BBT, or; b) the embodied cognition paradigm that emphasises practical engagement with environmental affordances that is determined by the total body, its needs, requirements and desires, and how the circularity of brain-body-world shapes the experiential totality (“world”, “umwelt”, whatever).

I also have one slight objection to your footnote on the Sage- Epictetus certainly did think the status of Sage had been attained by Socrates, and that it was thus possible to attain again.

At any rate, that’s my two cents. I’ve only recently come across your work after RSB’s guest post here. Started listening to the Rationally Speaking podcast and enjoying it a lot! I look forward to seeing more of your work on Stoicism and any possible dialogue!

“Towards a Corporealism”: http://attemptsatliving.wordpress.com/2013/02/28/corporealism1/

LikeLike

Massimo said

“That’s because that sentence by Marcus — like similar ones from other Stoics — can be interpreted both teleologically (which pretty much does require some kind of consciousness) as well as simply commenting on chairs of cause and effect (which doesn’t require any plan).”

and

“Our own consciousness and purposes are themselves the results of universal cause-effect.”

Consider that there is a difference between saying, on one hand, that the universe has One Big Plan (which presumably could theoretically be formulated in a concise english paragraph or two), and on the other hand, saying that the universe has (or makes plans). This would be the difference between saying the universe HAS ‘a’ teleology and that the universe is teleological. Or, that Massimo has one big plan and Massimo is a plan making organism.

Is it clear to you that the Stoics thought the universe had One Big Plan, or that they thought the absence of One Big Plan, means that the universe doesn’t have any plans? The universe clearly has many plans because we have them and we are part of the universe.

Now, when did these plans, which are the essence of our being, first exist?

Aurelius/Stoics say “the implication of causes was from eternity spinning the thread of your being”

Physicist Sean Carroll, presumably representative of many physicists, says that the future is as real as the past precisely because the past and future are completely implicit in the present moment. In saying so, he quotes Einstein (self proclaimed disciple of Spinoza–whose philosophy seems to reflect the ontology of the Aurelius quote above) as saying that “It appears therefore more natural to think of physical reality as a four dimensional existence, instead of, as hitherto, the evolution of a three dimensional existence.”

So, to say that the teleology we experience all around us, and in us, is a result of cause and effect in no way diminishes the fact that the universe is essentially and integrally teleological in the same way that our bodies are teleological. We give the universe purpose in the same way we give our bodies purpose, in that we use our environment for our plans as we do our bodies. We did not give ourselves the capacity to do this–this capacity was given to us by our bodies–which was in turn implicit in the universe ‘from eternity’. We can imagine that it ‘could have been’ otherwise, but that’s an imaginary universe that does not empirically exist.

LikeLike

The LOGOS Is Made of Elements Of Brain Simplified

The Logos started to dominate Greek philosophy with Heraclitus (circa 500 BCE).

Considering the importance of Neoplatonism for the Greco-Roman elite, Christianity had to make the Logos into god. Thus its importance precedes Logos Galileo’s statement that the book of nature is written in mathematical language. By the time of Galileo, the Logos had already become a research strategy: develop cute mathematics, and hope physics would follow.

(The notorious “Superstrings”, Not Even Wrong, is more of the same.)

The Logos scientific strategy started with Buridan. Kepler pursued it in his “War On Mars”: he tried all possible curves, and checked them against data. It took 30 years.

Calculus, developed initially by lawyer-mathematician Fermat gave Celestial Mechanics. Fourier analysis helped with heat, Poisson’s math predicted a dot to disprove the wave theory of light (thus proving the latter, as the dot was there!). Fitting mathematics to heat emissions forced Planck to introduce the Quantum.

Riemann discovered in the 1860s, the idea that force could be viewed as curvature (and reciprocally). Thus force predicted space. Einstein-Hilbert, and later Dirac, would that to good use, curving spacetime (1916), revealing spinors (1930). Spinors had been introduced in geometry by Élie Cartan in 1913.

How come the brain can predict the world?

It simple: the brain is built as a mini-world. Left to themselves, embryonic nerve cells organize themselves in mini-brains. Left to itself, having consulted with the world, the brain organizes its mini-worlds.

Substructures of the brains are mini-worlds. Made of what? Well, looking at neurons, or glial cells, we see networks made of varying materials (of axons, more or less covered with myelin, dendrites, and all sorts of protrusions, including inside synapses, and glial cells with their own networks).

All these variations mean very large dimensions (accentuated by 50 neurohormones and neurotransmitters), and all the entanglement mean highly non trivial topology (knots everywhere).

Some of these networks translate into sensations, discourses of sensations, or simply real discourses, and thus logic, as written by logicians, mathematicians and physicists.

The fact that the brain is physically made of immensely complex implications and neighborhoods means that it is made of the most complicated logos imaginable… For the good and simple reason that it is imagination incarnate.

This inner world, this world of the Logos, can be rebuilt better, and much more easily than the universe out there. Yet, it is informed, and initially greatly imprinted, by the universe.

Science consists into reproducing faithfully categorical structures as found out there (though experiments). (Here the word “categorical” is as found in a sense at least as complex as in modern Category Theory… Diagrams of arrows).

This, of course, does not differ from basic common sense: as the baby learns about gravity, it informs the proper Logos in the baby’s brain about the basics of gravity (science gets a bit more precise, but does not basically differ).

Control is about the inner world not contradicting too much the Universe’s Logos.

LikeLike

Hi Massimo,

An interesting article. Stoicism as you present it certainly does seem to be an admirable and surprisingly modern philosophy, so of ancient systems of thinking it seems to be one of the most worthy of adopting in contemporary times.

I also agree with you that all thoughtful people are in the business (or ought to be) of constructing coherent world views or philosophies.

Where I perhaps differ from you is that I don’t really see the point of updating ancient systems of philosophy for the modern era. I think it’s good to study the Cynics, Skeptics, Stoics, Epicureans, Buddhists, Confucianists etc, but I don’t understand why you would not just take a syncretic à la carte approach, taking a little bit from here and a little bit from there to form a world view personalised to your own tastes and views without feeling the need to call it neo-anything.

The problem I see with your approach is that you are trying to construct a plausible philosophy that adheres as closely as possible to the spirit of Stoicism, which it seems to me runs the risk of influencing and constraining you unnecessarily. I think you should only be trying to construct a plausible philosophy, without much concern regarding whether it meshes well with this or that school. Having a coherent, sensible, rational and useful world view is much more important than having one which aligns well with Stoicism, surely.

We’re both atheists, though we both had Catholic upbringings. This has probably shaped us to some extent, and some of the stuff Jesus said was pretty good. We could, I suppose, throw away all the supernatural and objectionable trappings of Christianity and update these teachings for the modern world, calling ourselves neo-Christians, but why would we do that, and is what you’re doing with neo-Stoicism any different?

LikeLike

Socratic,

“it still doesn’t seem to have the same emotional reaction as Cynicism does, and that acceptance, rather than contempt, is the Stoic approach”

I think you are right there. But the older I get the less I see the point of contempt, I suppose.

“I don’t think the Stoics had a developed critique of social convention”

I don’t think so either. But they certainly tried very consciously to act for the betterment of humanity, which at the least *implies* a critique of society.

Douglass,

“Though this does present a potential pitfall, which is in allowing values to taint facts”

Hmm, maybe, but that’s certainly not what the Stoics were after. They thought that the study of “physics” and logic was important precisely because one needs to understand reality and reason well in order to live a worthy life. Sounds like facts affecting values to me, not the other way around.

Seth,

“I think a model allowing for direct interaction and feedback among all 3 branches allowing for emergence of new progressive factors in the ethical branch might serve as a foundation for update”

Yes, and I’m pretty sure the Stoics themselves would agree. The egg is just a metaphor, and they used others. For instance, they proposed another analogy of philosophy as an animal, where logic is the skeleton, “physics” the flesh, and ethics the soul. Or philosophy as a field, with logic being the wall that marks it, “physics” the land and trees, and ethics the fruits. And so forth.

arranjames,

“the only other attempt I’ve seen (William B Irvine’s booK) was philosophically light and very unsatisfiying”

One of the problems with Irvine’s book, I think, is that he only focused on a subset of Stoicism, the parts he thought were directly applicable to modern life, without really trying to do justice to the whole thing. Maybe I should develop a book-length version of these two essays…

“Contemporary philosophical accounts of “nature” are more complex than the providential rational system of the Stoics”

Indeed, that’s one of the reasons to move from Stoicism to neo-Stoicism, as long as the “update” retains the spirit of the original. (If it doesn’t, that’s fine, but then I wouldn’t use the word Stoicism to label it.)

“CBT. This is really several problems … the use of philosophers like Epictetus must be able to distance itself from these critiques”

When I looked into it seemed to me that the evidence for the efficacy of CBT was pretty strong, certainly better than most other psychotherapies. But you are right, Stoicism as a philosophy does not and should not depend on the efficacy of a particular therapeutic practice, and much less from any entanglement btw that practice and questionable socioeconomic/political forces.

“The strains of eliminativism, whether it be the Churchland’s or RS Bakker’s brilliant BBT”

I don’t take eliminativism seriously, in my mind it is a fruitless effort, as it is mistaking ontology with epistemology (sure, “pain” is “just” the activation of C-fibers; no, this doesn’t mean human beings can do without talk of pain, psychological states, etc. to understand and navigate their world).

“the embodied cognition paradigm that emphasises practical engagement with environmental affordances that is determined by the total body”

I’m not sure why this would be a problem for Stoicism, but I need to think about it some more.

“Epictetus certainly did think the status of Sage had been attained by Socrates, and that it was thus possible to attain again.”

That’s not my understanding, but I’ll check.

“Started listening to the Rationally Speaking podcast and enjoying it a lot!”

Much appreciated!

Burgess,

“Or, that Massimo has one big plan and Massimo is a plan making organism”

That difference seems to me a minor one when it comes to the question of teleology. Whether I (or the universe) have one or many plans, I (or the universe) would still be acting teleologically. The problem for ancient Stoicism is that modern science has rejected a universal teleology, while retaining of course the idea that there are individual organisms that act purposely. So that part needs updating, and my proposal is to interpret the idea of a rational universe in neutral terms, Galileo-style.

“The universe clearly has many plans because we have them and we are part of the universe”

That confuses the whole with (some of) the parts, and it wouldn’t rescue the strong version of Stoic teleology.

“Physicist Sean Carroll, presumably representative of many physicists, says that the future is as real as the past precisely because the past and future are completely implicit in the present moment”

I like Sean, but he’s threading on treacherous metaphysical territory there.

“to say that the teleology we experience all around us, and in us, is a result of cause and effect in no way diminishes the fact that the universe is essentially and integrally teleological in the same way that our bodies are teleological”

I disagree, for the reasons given above.

Patrice,

“The LOGOS Is Made of Elements Of Brain Simplified”

I’m afraid I can’t imagine what this means.

“Christianity had to make the Logos into god”

The Stoics were talking about Logos / Nature / God / Zeus well before Christianity.

The rest of your comment is interesting (though I’m pretty sure historians of science would pick several issues with your views), but I fail to see what it has to do with Stoicism.

“Where I perhaps differ from you is that I don’t really see the point of updating ancient systems of philosophy for the modern era”

Well, my friend, unlike you I see much value in what has been done by people before our generation, and even, incredibly, before science…

“I don’t understand why you would not just take a syncretic à la carte approach”

Too pragmatic, and therefore too open to the danger of picking and choosing what I want.

“without feeling the need to call it neo-anything”

I think there is value in tradition and paying due to those who came before us.

“which it seems to me runs the risk of influencing and constraining you unnecessarily”

It’s an ongoing project, it may as yet fail.

“Having a coherent, sensible, rational and useful world view is much more important than having one which aligns well with Stoicism, surely.”

Yes, but one has to buy in one set of fundamental assumptions or another, and I happen to think that the Stoic view of what constitutes the happy life (which, of course, is one version of the ancient Greek-Roman view) is invaluable and ought to be retained.

“We could, I suppose, throw away all the supernatural and objectionable trappings of Christianity and update these teachings for the modern world, calling ourselves neo-Christians, but why would we do that”

Some people actually do precisely that. But I find more value in Zeno and his followers than in Jesus.

LikeLike

Disagreeable Me, I’d like to try an answer in place of Massimo for your excellent question.

In principle of course you are right. As modernists, we will take a syncretic approach, adopting what we want and discarding what we don’t from any given tradition.

As an aside, this is really no different from religious believers: although many will claim they are not, we know that the Bible and later Christian theology is rife with internal contradictions. In order to make any sort of coherent sense of it one must pick and choose, whether that’s overlooking some obtuse passage in the Bible or agreeing with Augustine that belief should cohere with science. Looked at carefully, there really is no such thing as a non-syncretic approach to belief, even religious belief.

That said, there are clearly degrees. One reason I am interested in secularizing early Buddhism is that I find it generally a wise and congenial teaching. While there is much to be gained from wholesale syncretism, there is also something to be said for not reinventing the wheel, so to say. “Coherent world views” are not a dime a dozen, not well-thought-out ones anyhow; they take time and effort. Why not look to the past to see if much of that work has already been done by someone, or some group of people? Then take the framework and discard whatever we know is unworkable. That’s a great starting place.

Insofar as we take a lot from one school, as I would early Buddhism, or Massimo Stoicism, we may decide to call ourselves neo-Stoics, or secular Buddhists, or whatever. If we only take a phrase or two here and there we may simply nod to them once in awhile, as say I would for Aristotelianism. I find much to agree with in Stoicism, and read them profitably, and plan to continue reading the Stoics in the future to learn from their insights and mistakes. I could even be a neo-Stoic, depending on how that was understood. But all things considered my affinities probably lie closer to early Buddhism.

Another related question is why we look so far into the past. For my own sake, it’s that some early (Classical, Indian) approaches to philosophy are more in tune with a ‘path to practice’, as I put it before. Modern philosophy at least since Descartes, great though it is, has tended more towards refining true belief than towards eudaimonic practice. Perhaps this comes out of its roots in the creedalism of Christianity, who knows? But although getting to true beliefs is critical, that is far from the whole story for eudaimonia.

If you agree with this sort of approach, then there are some very great thinkers who have already done a lot of the footwork for you. Why not make use of them? Insofar as you find yourself being thoroughly syncretic, not agreeing much with any of them but making a kind of soup of their views, then perhaps calling yourself neo-this or secular-that will not illuminate anything. But insofar as you find the approach in one school particularly compelling, a label like ‘secular Buddhist’ can at least be a useful shorthand, if in the final analysis it will always require unpacking.

But then as I say, even someone calling himself a Christian, or an atheist, or a secularist, or an analytic philosopher will require its own unpacking.

So long as we are not clinging to labels, adopting some position which we know is false simply because it falls under our preferred system, be it Buddhism, Stoicism, or what have you, I don’t think there’s a real problem here. The main issue with labels is ease of communication.

LikeLike

Pretty much what Douglass said.

LikeLike

Hi Massimo and Douglass,

Thanks Massimo, and I also think Douglass’s answer is very good, but I just wanted to clarify a few points Massimo seems to have misinterpreted a little.

> Well, my friend, unlike you I see much value in what has been done by people before our generation, and even, incredibly, before science…

I never said I didn’t see value in it. In fact I said I did see the value, but that I don’t see why we should try to adopt philosophical systems wholesale. My point is that the Stoics and the Epicureans and the Cynics and the Buddhists etc all have valuable insights and don’t see why we should try to force ourselves into one particular philosophy.

> Too pragmatic, and therefore too open to the danger of picking and choosing what I want.

And what’s wrong with that? That’s what you’re doing at a coarse-grained level anyway. You find Stoicism more attractive than Buddhism so you pick and choose Stoicism over Buddhism. I don’t see the harm in adopting this approach at a finer grain, keeping in mind that you actually want (I imagine!) is not just to reach self-serving conclusions but to be intellectually honest, moral and consistent.

I feel Douglass’s response is more plausible, which is that it for some people there are ancient schools of thought which feel right enough to survive this fine-grained picking and choosing relatively intact, and so presumably the label “Stoic” is appropriate for you because the amount of Stoic thought you feel like rejecting is relatively minimal or of less significance. Certainly you would be rejecting less of Stoicism than I would of Christianity.

> It’s an ongoing project, it may as yet fail.

Out of curiosity, how would you measure failure? By finding inconsistencies? By reaching conclusions you didn’t like? By failing to achieve eudaimonia?

Anyway, I can certainly see the value in what you’re doing, and I am somewhat persuaded, but I remain worried that it is dangerous to be too attached to a particular school because of the risk that it may limit imagination or open-mindedness. I guess I’m just too much of a contrarian to be a fan of any kind of orthodoxy, ancient or modern.

LikeLike

Labeling Philosophy

I go by the name of I, which is synonymous with everything.

And unlike Descartes who found I and then sadly got lost again, I will (free will) stay just here. =

LikeLike

Massimo,

on the evidence base of CBT it’d be worth looking into studies of evidence-based medicine and evidence-based practice and how the standards and protocols are biased towards certain interventions and outcomes in their very design. This is discussed to a good degree in Richard Bentall’s Doctoring the Mind: why psychiatric treatments fail, Paul Maloney’s The Therapy Industry, and throughout David Smail’s books. There is also a lot of be gained from looking to the value-based practice discourse that operates as a response to EBP. Elsewhere there is a healthy literature on CBT’s ideological adaptiveness to individualist neoliberal capitalism and its role as a quick fix. This literature is ample- David Smail again was one of the leading voices on this. There have also been a good deal of long-term studies showing that the real gains that CBT undoubtedly does make with some people doesn’t last very long at all. Some think this indicates CBT is a good plaster for symptom covering without ever tackling the causes of problems. I am not claiming CBT is utterly worthless, but that it is ideologically compromised and scientifically inflated.

I agree with what you say about eliminativism except that I would mark the problem differently. It is possible that eliminativism is a true ontological set of facts and commitments but this means nothing in terms of human coping-with. We will retain our current phenomenal experience and “folk-theories” for as long as we live. We will, however, shuttle back and forth between the Scientific and the Manifest Images. That is, eliminativism, if true, updates out naive self-understandings. Moving beyond this, into the realms imagined by people like David Roden, we are reaching the point where we can postulate the transition to posthuman life as a genuine possibility. With technological advancement being what it is (I’m thinking of AI, robotics, advances in neuromodulation) we’re getting to the point where humanity could pass into being a new and unpredictable kind of being- one for whom new values, which we may not be able to imagine, take hold. This is approaching us as an increasingly empirical possibility. With this kind of possible future it may be that posthumans will be born out of the literal elimination of what we currently experience as subjectivity, selfhood, being a person and so on.

All of that said, I am a backer of the embodied-enactivist positions. The reason these are a problem for Stoicism is that they fundamentally part ways with the cognitive-rationalism of the Stoic psychology. The idea that our mind receives impressions that reason then goes on to judge, this is an internalist picture that embodied cognition, at least in the more enactivist or action-oriented perspectives, is opposed to. This is too big a problem for me to go into in this post- but we just need to consider ideas like those of Hutto on contentless minds, or the idea that the body isn’t just an accessory or vehicle to thought but that morphology and sensorimotor capacities determine the forms of cognition possible to us.

LikeLike

Disagreeable Me I agree that it can be “dangerous to be too attached to a particular school because of the risk that it may limit imagination or open-mindedness”- this is why I would see any updated Stoicism as being part of a broader transversal assemblage in which heterogeneous particles (practico-theoretical, infrastructural, therapeutics, so on) are able to develop a coherency that doesn’t coagulate into a frozen philosophy divorced from living or that is incapable of being sensible of and responsive too our entire horizon of possibilities. I situate this- along with a few other folk- as a response to the various catastrophes (real or imagined) that we are undergoing and thus call it a postnihilist praxis (cf syntheticzero.net).

At the same time it is important to remember that Stoicism itself was hardly dogmatic. Between Zeno and Marcus we see a massive political shift, and we can see from Epictetus’s use of a personalised concept of God that he is operating within a shifting theological landscape, while Stoics like Seneca make frequent reference to Epicurus and his followers. Indeed, much later you get someone like Montaigne who is often characterised as a Stoic but who doesn’t resemble Chyrissipus or Epictetus all that much. And looking to contemporary uses of Stoicism, such as in Martha nussbaum’s work on the therapy of desire, we can also say that Stoicism has been exposed to psychoanalysis, or with Deleuze that it has been placed into a lineage that includes Spinoza. Stoicism isn’t a closed system. Indeed, as Massimo and I both emphasise, it is required that a neoStoicism would not be identical to the Stoicism of old. Whenever we read the Ancients we should remember their context, but if we care about what value they have for us we must also read them in relation to our own conceptions of things. This necessarily means that an updated Stoicism may be a philosophical activity that the Stoics might not even recognise. That is what fidelity to their work means.

LikeLike

Hi Massimo,

I’m glad to see that the annual Stoic Week is approaching at University of London, it seems that the spirit of Zeno and Chrysippus is alive.

It is interesting what SocraticGadfly wrote: “I see Cynicism as having some influence on Sufi Islam as well as certain strains of Christian denialism like the holy fool.”

I’ve read that the first Cynics referred to an old tradition that influenced the Greek and Asian culture according to a common pattern. The vagaries of such old tradition are beyond my knowledge, but, along with Socratic comment, it sounds plausible. On the other hand, it is also plausible that the former Cynics that landed and sprung in Athens were close to a web of people, lovers of philosophy, settled throughout the Greek cultural and territorial sphere. Curiously, Diogenes, Crates and his wife Hipparchia were rich people though gave away their money to live a life of poverty on the streets. This life style resembles the life of the first Christians.

With regard to the holy fool, one of the most famous was the Syrian Simeon that was close to Jesus’ teaching. He spent many years in desert near the Dead Sea practicing asceticism and spiritual exercises and after moved to Emesa to perform social and charitable services. Once in that city he behaved like Diogenes in Athens, upsetting conventional rules.

The target of his invectives were the rich, thieves and lustful. Simeon entered the gate of Emesa dragging a dead dog, this animal was the Cynics’ logo. Like Diogenes, he suffered insults and beatings by playing the fool, it seems that Simeon endured it with stoicism. He was considered a holy man and his saintly deeds were done secretly.

Simeon died about 570 AD and was buried in the same mass grave where the homeless and foreigners. While the body of Simeon was carried, several people heard a wondrous celestial choir. After his death the secret of his imitative foolishness come to light, his peers remembered his acts of kindness and reported striking miracles. There are some aspects of the ancient times that are difficult to fit in today’s sight, though, quite often, they are seen with mockery and disdain.

LikeLike

Massimo, regarding our discussion of teleology, it seems you are abandoning the central Stoic doctrine of monism. The idea that everything is made up of one kind of substance–i.e. atoms is not really a sufficient expression of this monism is it? The atoms are configured in a certain way and regardless of how that came to be, in terms of external causes, that configuration is One Cosmos and everything this Cosmos does is an act of that Cosmos.