In some circles, the writings of Jacques Lacan are revered as a source of deep insight into the human psyche and the nature of language and reality. In saner quarters, however, the French psychiatrist is denounced as an intellectual charlatan: a purveyor of obscure and impenetrable nonsense. Lacan was one of the prime targets of Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont’s Intellectual Impostors, the book-length criticism of postmodern nonsense that followed the famous hoax that Sokal perpetrated on the journal Social Text [1].

Many people who read Lacan, or see him at work in some of the available YouTube clips, find it hard to believe that anyone can take him seriously. In a new paper with philosopher of language Filip Buekens, published in the journal Theoria, we explored Lacanian psychoanalysis as a case study in the psychological and epistemic mechanisms of obscurantism [2]. On the one hand, we develop cognitive explanations for the allure of obscure prose. On the other hand, we explain how the particular structure and content of Lacan’s theory facilitates the overextension of the cognitive heuristics that make us vulnerable to obscurantism.

How is it possible for the reader to be taken in by the impenetrable pronouncements of — as we shall call him — The Master? The first thing to note is that, in everyday life, it sometimes makes perfect sense to accept a statement before fully grasping it. For example, children accept what adults tell them even before they understand precisely what they are supposed to believe. People endorse the equation of special relativity (E=mc²) or the reality of economic recession while having only the foggiest idea of what such claims really amount to. This willingness to accept an obscure utterance for the nonce, without knowing what exactly was on the speaker’s mind, may actually facilitate the learning process. If you insist on understanding every single word of what you are told, before proceeding to the next step, you may not get very far. Better to bracket those obscure parts and trust that you will figure out their exact meaning later on.

In line with the principle of charity in cooperative communication, people will try to reconstruct the meaning of unknown terms on the presumption that what the speaker utters is true and relevant — particularly when they defer to the speaker as an authority. If what the speaker asserts seem bizarre or false on its face, it is prudent to suspect that the problem lies with your interpretation. The cognitive scientist Dan Sperber has called such utterances, swallowed without proper understanding, “semi-propositional ideas” [3].

As with all mental heuristics, this charitable attitude towards speakers, particularly ones regarded as experts, is liable to exploitation. Not everything that is obscure or apparently bizarre will eventually resolve into something true and relevant.

But then people will find out at some point, won’t they? Not necessarily. Another well-known psychological mechanism may kick in and prevent the listener from stopping the hermeneutic search for meaning after diminishing returns have set in. Psychologists have long known that people are averse to losses. Interpreting obscure prose is a form of cognitive investment, an expenditure of time and energy. If there is no hidden meaning to be found after all, your cognitive efforts will have been wasted. People are reluctant to face their losses, and tend to hold on to assets that have long since failed to deliver any returns.

In a similar vein, someone who has spent years wading through obscure prose will have a hard time facing up to reality and admitting that she has been duped. This is especially true when the quest for meaning is an open-ended one. For all you know, treasure may still be lurking deeper down, if only you are prepared to dig a little further — if only you spend a little more time and effort interpreting The Master’s writings. Some fine day perhaps the truth will dawn on you, or perhaps it never will — there is no way to know except by trying.

To make matters worse, people may persevere in a futile hermeneutic quest because — taking up the investment analogy again — they conjure up imaginary returns. In financial investments, however, at least the losses and gains can be objectively measured, they appear as hard figures on a balance sheet. In the quest for meaning identifying the long-sought treasure is less straightforward. In the hope of rationalizing his investment, the interpreter may be tempted to project all sorts of less-than-exciting “insights” onto the Master’s writings, such as common-sense knowledge or psychological lore. Alternatively, she can read her own musings into the Master’s pronouncements, thus using the latter as a mouthpiece. Naturally, obscure writings are perfect vehicles for such ventriloquism. Psychologists have identified the Forer effect: interpreters tend to read specific claims into obscure statements, mistaking their own creative interpretations for the author’s intended meaning. As Richard Webster wrote, “its very vagueness and obscurity means that it is pregnant with semantic possibilities” [4]. In line with Forer’s observations, this creates an illusion of intimacy: Lacan’s students had the impression that he was speaking for them and for them alone, revealing his insights in a secret code. Everyone ends up understanding The Master — but they all disagree about what is being said.

Black holes in the sky

These psychological mechanisms are fairly well-known, but they only tell part of the story. What is striking about Lacanian psychoanalysis is that it facilitates the slippery slope I just described, by accommodating for those psychological effects within its very theoretical framework [5]. Indeed, it seems almost designed to seduce the reader into an endless hermeneutic quest, and to shut down any critical questions that may arise in the process.

Lacan’s pronouncements are couched in a number of arcane concepts — the Other, the Symbolic, the objet petit a, jouissance, the Phallus, etc. — that are notoriously difficult to define. The central tenets of Lacanian theory, to the extent that one can make sense of them, are that the unconscious is structured like a language and that human beings are trapped in a web of signifiers. Communication is a failure, language is a prison, and our deepest desires remain frustrated. In Lacan’s linguistic re-interpretation of Freud’s Oedipus complex, subjects are symbolically castrated upon introduction in the Symbolic order. By means of obscure pseudo-mathematical formulas, Lacan has tried to show that the Real can never be fully accounted for by the Symbolic order. There always remains an ineluctable loss, something that defies understanding and remains elusive. This thing that cannot be grasped or comprehended, which plays a central role in Lacanian psychoanalysis, has been theorized as the “objet petit a.” It is like a vanishing point, always out of reach. Or as The Master wrote: “The objet petit a is what remains irreducible in the advent of the subject at the locus of the other.” The later Lacan coined the term “sinthome” for that which is beyond meaning in his so-called topology of the human mind. Meaning is always manifold and interpretation ambivalent, determined by a web of unconscious associations that we can barely glimpse. As a consequence, communication is doomed to fail, our identity is fragmented and divisive, and truth has a fictional structure.

If one looks at these Lacanian mantras, it is striking how well they exemplify the experience of trying to make sense of Lacan’s own writings. After all, what better illustration of the primacy of the signifier over the signified and the elusiveness of meaning than Lacan’s own ever-shifting and esoteric concepts? The doctrine itself tends to acquiesce the interpreter into the frustrating experience of trying to make sense of it. If you don’t understand, you must be on the right track. Lacan’s style of exposition, some followers have suggested, mimics the language of the unconscious. Or, to put in in Lacanese, the unconscious speaks through Lacan. Unfortunately, Lacanians have mistaken the predicament of their own belief system for that of every other discourse. Paraphrasing Karl Kraus, one of Freud’s earliest critics, Lacanian psychoanalysis is itself the disease for which it claims to be the cure.

By anticipating and accounting for the readers’ feeling of disarray and puzzlement, Lacan’s theory not only facilitates a futile quest for meaning, but also provides a protective shield against criticism. To bemoan Lacan’s obscure language, from the Lacanian’s own point of view, is to refuse to understand the deeply subversive nature of Lacan’s teachings about meaning and truth. To insist on clarity of language is to miss the very point of Lacan. Thus, the diligent interpreter is kept under The Master’s spell. The philosopher Stephen Law, in his book Believing Bullshit [6], has likened such belief systems to black holes, constructed in such a way that “unwary passersby can find themselves similarly drawn in,” never to escape again.

Let There Be More Light

Obscurantism is a symptom of a degenerating belief system. It arises whenever one needs to defend what is (no longer) defensible. Just as Freud’s theory was collapsing under its own implausibility, Lacan’s obfuscations came to the rescue. For instance, Lacan recast the traditional Freudian Oedipus complex — where a boy wants to kill his father and have sex with his mother — as an abstruse psycholinguistic drama, where physical castration becomes a symbolic amputation through the entry into language, and the capitalized Fallus is equated with the imaginary square root of -1. Freud’s theory was difficult to falsify, but at least it could be comprehended. In Lacan’s hands, the Freudian edifice was lifted out of the realm of meaning altogether. In spite of this radical departure from orthodoxy, Lacan presented his theory as a return to the founding texts, to whatever it is that they have always meant.

Of course, nowhere is this need for obfuscation more pressing than in theology. God used to be an invisible agent in the heavens with human-like emotions, listening to prayers and performing miracles on earth. Nowadays, he has retired from that role and lives on as some ineffable Ground of Being, hardly capable of existing in the mundane sense, let alone revealing himself on earth or performing miracles. After every retreat, however, theologians will often insist that this is what they meant all along [7].

But what if postmodern theology or Lacanian psychoanalysis is just too sophisticated and profound for philistines like us? What if the illusion of depth is not an illusion at all? Perhaps the proof of the pudding is in the eating. A couple of years ago, I made my own pudding, just to see if anyone out there was ready to swallow it. I wrote an abstract full of obscure gobbledygook and submitted it to two theology conferences, under the pseudonym Robert A. Maundy (an anagram). It was partly constructed as a parody of John Haught’s book God After Darwin, which had exasperated me with its nebulous prose. Both conferences accepted the abstract without any problem, presumably after sending it out for peer review [8]. After the hoax had been exposed, one of the conference organizers argued, in his own defense, that he gave my submission the benefit of the doubt, because “postmodern theology can often be somewhat impenetrable.” Quite so.

In the case of Jacques Lacan or postmodern theology, we can never be sure if there is not some hidden meaning that we fail to grasp. In the case of Robert A. Maundy, however, I can assure you that none is to be found (unless God is using me as his vessel). Every single sentence of it is meaningless. In fact, the abstract was largely written in reverse order, to avoid meaningful connections between the sentences. As it turns out, it’s not easy to keep meaningful interpretations at bay, because the human brain (or mine at any rate) wants to construct a coherent narrative. I tried to keep my focus on grammar and syntax, and as for the vocabulary, I was just dipping my spoon in the unctuous soup of Sophisticated Theology (the obligatory snipe at Richard Dawkins probably also worked as a lubricant). As soon as some part started to make sense, it went out of the window. As it happens, my collaborator Filip Buekens, who wrote a devastating study of Lacan and his followers in Dutch, also wrote a parody abstract under Robert Maundy’s name, on the ineffable object petit a with regard to “anal male discourse” [9]. We’ll get back to this.

Obscurantist Strategies

It is useful to have a look at the book that has been most recently hailed as the pièce de résistance of theology, which will leave all atheists fuming at the sidelines. Ironically, David Bentley Hart’s intention in Experiencing God is merely to clarify the meaning of the word God. Some would call that a particularly egregious example of false advertising. After wading through many pages of pedantic prose, all the reader is left with are a number of obscure and contradictory phrases, invariably capitalized or prefixed with superlatives, supposedly capturing the nature of God’s existence. For example, we learn that God is the “transcendent actuality of all things and all knowing, the logically inevitable Absolute upon which the contingent depends,” that he is the “infinite wellspring of all that is” and also “simplicity itself, the very simplicity of the simple, indwelling all things as the very source of their being.”

This brings us back to the principle of interpretive charity. A classical strategy of the obscurantist is to say something prima facie absurd, or to juxtapose two apparently contradictory claims. For example, Hart claims that God is “not a being but is at once ‘beyond being’ (in the sense that he transcends the totality of existing things) and also absolute “Being itself” (in the sense that he is the source and ground of all things)” [10]. The trick is content-free and can be repeated with any adjective: “He is not just something X, but X-ness itself, the uncaused source and ground by which finite X-ness [is] created and sustained” [11]. (Can you guess which adjective Hart used in this case?)

So God is simultaneously not a being, beyond being, and Being itself. The strategy exploits our interpretive charity: the contradiction is so palpable that we assume the writer must have meant something different and more profound. God is also “beyond my utmost heights” and “more inward to me than my inmost depths.” So, both extremes at the same time? As Bob Maundy put it, he is “an absolute Order which both engenders and withholds meaning.”

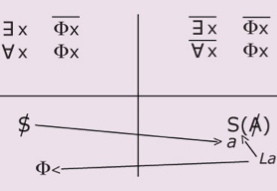

Not to be outdone, Jacques Lacan has offered us the most exquisite example of this strategy. In his formulas of sexuation, describing the phallic function in relation to the desiring subject, he presents us with the following diagram of masculine and feminine sexuality.

The right-hand column describes feminine sexuality, the left-hand column its male counterpart. Now, as any student of logic will spot right away, not only do the two formulas in each column contradict each other, but the columns themselves are restating the same contradiction: 1) everyone is submitted to the phallic function; 2) there exists someone who is not submitted to the phallic function.

Because the contradiction is so obvious, at least for someone with a grasp of elementary logic, the reader is tempted to conclude that Lacan must have meant something more profound. The rest is left to the creative imagination of the reader. Ever since, commentators have dreamt up interpretations to make sense of the formulas of sexuation, but no consensus seems to be in the offing (“well yes, that is the ineffable objet petit a of understanding!”). The paradoxes of sexuation also provide the framework for Robert A. Maundy’s second abstract on anal male discourse.

Postmodern philosophers are quite fond of stating such provocative contradictions or outright absurdities: other one-liners by Lacan include “la femme n’existe pas” and “Il n’y pas de rapport sexuel chez l’être parlant” (there is no sexual relationship in the speaking subject). The deconstructivist Jacques Derrida claimed that “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte” (there is nothing beyond the text) and Jean Baudrillard wrote a whole book about why “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place.” Stephen Law advises aspiring gurus to work around cryptic contradictions: “The great beauty of such comments is that they make your audience do the work for you.”

Such tantalizing claims often vacillate between some straightforward yet absurd interpretation, and a sensible but trite one. For example, of course “the woman” as such does not exist, as no two women are exactly similar. And naturally, what happened during the Gulf War is partly open to historical interpretation. Did we need the postmodern savants to tell us that? The strategy appeals to interpretive charity on both fronts: we assume that the speaker must have meant something more profound than the banality, but we also assume that he could not possibly have intended the absurd interpretation. Daniel Dennett called this a Deepity [12] and uses the example “Love is just a word.” If you put scare quotes around ‘love,’ the claim is trivial. If you read it at face value, it doesn’t make any sense. Whatever love is (an emotion, some neurochemical process), it is not composed of letters.

Postmodern discourse, which is heavily indebted to Jacques Lacan, is full of such Deepities: “Truth is just a social construction,” “Reality is another kind of fiction.” Philosopher Nicholas Shackel has compared this strategy to a medieval defense tactic in which a defensible stone tower (the Motte) is surrounded by an area of open land (the Bailey):

For my purposes the desirable but only lightly defensible territory of […] the Bailey, represents a philosophical doctrine or position with similar properties: desirable to its proponent but only lightly defensible. The Motte is the defensible but undesired position to which one retreats when hard pressed. [13]

Intellectual intimidation

It is important to emphasize the intimidating effect of unintelligible prose. In the midst of people who all profess to understand what is being said, it takes courage to stand up and admit that you don’t. The philosopher Paul Ricoeur was brave enough to admit, after attending one of Lacan’s seminars, that he did not understand a word of what was being said, even though he found himself in the company of people who seemed to be in the knowing. Many interpreters have boasted that they, for one, understand Lacan perfectly well. The philosopher Jean-Claude Milner has maintained that the man’s writings are in fact crystal-clear, despite appearances to the contrary, and are hardly in need of any interpretation. Who will be confident enough, after years of investment in Lacanian exegesis, to see through this rhetorical bluster?

In his latest book, David Bentley Hart spends a lot of time lamenting the intellectual poverty of our age and hectoring his (atheist) readers, calling them out for their abysmal ignorance and their puerile misunderstandings. Lacan was fond of insulting and belittling those in his audience who failed to understand him. In a television appearance in 1974, he announced that most of his audience were “idiots,” and that he was surely mistaken to descend to their level. Intellectually insecure readers felt that the difficulty of Lacan’s prose was erected as a natural barrier for excluding those unworthy of his insights. Only the best divers could access the most precious pearls. As Lacan himelf wrote: “If you don’t understand them [my writings], so much the better, it will give you the opportunity to explain them.”

Obscurantism is a means for creating anxiety and insecurity about not understanding. This phenomenon has an important social dimension, as in Hans Christian Andersen’s story about the emperor who orders a new suit of clothes that, as the tailors assure him, are invisible to those that are either unfit for their positions, stupid, or incompetent. When the Emperor flaunts his new cloths on the streets, everybody can see that he is naked, yet nobody dares to point it out. But as soon as one child cries out that the emperor isn’t wearing anything at all, the spell is broken and everybody starts laughing. Many of the followers of Lacan are undoubtedly sincere, because they have spun their own interpretive fabric around their naked emperor. But the social dynamic is the same. It only takes a couple of sycophants, and a large measure of intellectual insecurity, to make sure that no-one dares to challenge the emperor. The seduction of obscurantism therefore has a self-reinforcing social dynamic.

There are of course many differences between the cult of Lacan and postmodern theology. In the case of theology, we have to take into account its ambivalent relation with popular religion. On the one hand, it takes a distance from the anthropomorphism of folk religion, but on the other hand, it remains attached on its leash. As the philosopher Robert McCauley wrote: “Theology, like Lot’s wife, cannot avoid the persistent temptation to look back — to look back to popular religious forms.” [14] Most religious believers have no idea about the arcane lucubrations of theologians, but the intimidating jargon of academic theology assures them that religious faith is still intellectually respectable, and that those simple-minded atheists have fundamentally misunderstood what religion is all about. In that sense, theology functions as an intellectual fig leaf for popular religion. In any, case, the self-protective rationale of obscurantism in both belief systems seems to be the same. Darkness provides a safe haven from the light of evidence and reason. According to Augustine, the serpent in the Genesis story was sentenced to grovel in the mud for committing the sin of curiosity. Expelled from the garden of Eden, he was forced to “penetrate the obscure and shadowy.” Make of that what you wish.

_____

Maarten Boudry is a philosopher of science and postdoctoral researcher at Ghent University. In 2011, he defended his dissertation on pseudoscience: Here Be Dragons. Exploring the Hinterland of Science. He is co-author of a Dutch book on critical thinking (2011), together with Johan Braeckman and co-editor, together with Massimo Pigliucci, of Philosophy of Pseudoscience: Reconsidering the Demarcation Problem.

(Thanks to Stephen Law and Filip Buekens for their comments! Parts of this essay were published before at the Epistemic Innocence blog.)

[1] Sokal, Alan, and Jean Bricmont. 1997. Impostures Intellectuelles. Paris: Jacob. For a contribution of Sokal to SciSal see here, here, and here.

[2] Buekens, Filip, and Maarten Boudry. 2014. “The Dark Side of the Loon. Explaining the Temptations of Obscurantism,” Theoria.

[3] Sperber, D., F. Clément, C. Heintz, O. Mascaro, H. Mercier, G. Origgi, and D. Wilson. 2010. “Epistemic Vigilance,” Mind & Language 25(4):359–393.

[4] Webster, Richard. 2002. “The Cult of Lacan: Freud, Lacan and the Mirror Stage,” richardwebster.net.

[5] Boudry, Maarten, and Johan Braeckman. 2012. “How Convenient! The Epistemic Rationale of Self-Validating Belief Systems,” Philosophical Psychology 25(3):341-364.

[6] Law, Stephen. 2011. Believing Bullshit: How Not to Get Sucked into an Intellectual Black Hole. New York: Prometheus.

[7] This is not to say that all modern theology is obscurantist. Theologians such as Richard Swinburne and William Lane Craig have tried to defend the traditional tenets of faith in a pretty straightforward manner, without much recourse to obfuscation.

[8] The abstract is still listed in the proceedings of the Reformational Philosophy conference. To the best of my knowledge, the other ones are authentic, but don’t take my word for it.

[9] Both abstracts can be found on Bob’s website.

[10] The claim is repeated a couple of times: “In one sense he is ‘beyond being,’ if by ‘being’ one means the totality of discrete, finite things. In another sense he is ‘being itself.’”

[11] In case you are wondering how this works, it is just a matter of God “pouring forth its infinite actuality in the finite vessels of individual essences.”

[12] Dennett, Daniel C. 2013. Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking: WW Norton & Company.

[13] Shackel, Nicholas. 2005. “The Vacuity of Postmodern Methodology,” Metaphilosophy 36(3):295-320.

[14] McCauley, Robert N. 2010. “How Science and Religion Are More Like Theology and Commonsense Explanations Than They Are Like Each Other: A Cognitive Account,” in D. Wiene and P. Pachis (eds.), Chasing Down Religion: In the Sights of History and Cognitive Science: A Festschrift in Honor of Luther Martin Thessaloniki: Barbounakis, 242-265.

Hi Disagreeable

I would never have thought I could say ‘Hi diagreeable’ to someone without being funny or mean!

I marked up my previous post using bbcode, but apparently that doesn’t work on this blog. I’ll try HTML this time.

Yes, I would love a preview button and instructions about the markup language.

You wrote:

IMHO, saying that you can learn philosophical analysis by studying only modern texts is like saying that you can learn biology by dissecting a few rodents, e.g. a rat, a mouse, a lemming and a gerbil.

A typical course on vertebrate biology includes dissections of representatives of the different classes of vertebrates, say lamprey, shark, rudd or perch, mud puppy and/or frog, chicken or pigeon, and cat or rat.

Dissecting a few rodents instead of those classics would perhaps be enough to acquire dissecting skills and (to a lesser extent) the ability to relate 2-D schemes to the 3-D structure of animal, but it would not help you with many other skills fostered by the dissections, such as the development of feeling for and insight in the relation between the different classes of vertebrates, the ability to see a certain specimen as both a representative of its class, a representative of its species and an animal with individual characteristics, a notion of the empirical content of concepts as homology and adaptation, the ability to generate questions about what you see, the ability to discuss observations and their meaning with peers, the ability to cope with the frustration inherent to experimental work etc. etc.

If you try to learn philosophy by studying modern texts only, you would miss much of how these texts hang together, you would not develop your ability to familiarize yourself with strange conceptual frameworks, you would not develop your ability to evaluate and criticize those frameworks, you would not practice you ability to provide solutions for problems within such frameworks and you would miss the joy of coming to understand ideas that initially seem outrageous and of developing doubts about ideas that seemed obvious.

I can agree that reconstructing the history of conceptual frameworks is not *the* goal of philosophy (actually, I have no idea whether philosophy has a goal and what it would be). Nevertheless, I think that that reconstruction is an important part of philosophy. It is necessary to understand, discuss and improve conceptual frameworks and understanding, discussing and improving conceptual frameworks is one of the thinks that makes a philosopher into a philosopher.

In other words, saying that you can do philosophy without reconstructing the history of conceptual frameworks is like saying that you can completely understand current life without reconstructing its evolutionary history.

Sure, who would deny that? However, nobody in this discussion said that the reason why it is important for philosophers to study old texts is that it helps them to generate good ideas.

Here are some reasons that were given:

Aravis Tarkheena:

Massimo Pigliucci:

As I have indicated elsewhere on this thread, I don’t know whether Lacan or critics like Wollheim (himself a supporter of Freud) are correct or not. I thought Boudry to not have substantively engaged with Lacan as Wollheim did and thus to have presented a very shallow case. Further, I find his co-written article which he cited to me as evidence that psychoanalysis *as a whole* is pseudoscience to be unpersuasive, although in it he clearly states that psychoanalysis “fits the bill” (p. 176) in terms of a pseudoscience to which social constructivism can be applied. I see nothing whatsoever in the article about the difficulty of disproving psychoanalysis and nothing he has said in this thread is inconsistent with that. I gather from what you have said that your view is more conservative in terms of the ability to demonstrate that psychoanalysis is pseudoscience and thus avoids some of the problems I see with Boudry.

It is one thing to talk about philosophy of mind. It is another altogether to talk about health care professionals legally governed by a standard of care and regulated by state laws. If you believe that psychoanalysis or some subset of it authorized by the APA is “wrong, incoherant, and ungrounded” then, since we are talking about health care professionals, the question of harm arises immediately. There is no issue of harm with a philosopher of mind who presents a paper with which you disagree and which you think is wrong, incoherent, and ungrounded. The question of harm immediately raises its head here, since psychoanalysis inevitably involves patient care. Therefore, if Lacanian psychoanalysis and, for Boudry, *all psychoanalysis* “fits the bill” in terms of being a pseudoscience who falsity is demonstrable, then either all non-psychoanalytic members of the APA are allowing what to critics like Boudry is a straightforwardly unscientific approach (in which case they are allowing patients to be deceived by their psychoanalytic colleagues) or they are all under mass hypnosis. And no, ignorance is not an option, not if psychoanalysis is as obviously false as Boudry claims. Given their training and education, if Boudry and critics of psychoanalysis are correct, I would say the former is more likely to be the case.

LikeLike

Hi Coel,

Probably not.

Probably, but not entirely. You need some innate instinctive information processing ability to bootstrap the whole enterprise. Children learn through play, but without some innate ability to learn they would be no different from your oak tree. So though, as you say, reason and experience may be intertwined, we need to have some sort of innate programming which was arrived at through evolution even if that can only be brought to fruition by interacting with the environment.

Another problem arises when we start to draw conclusions using our developed reasoning abilities. When we can verify our predictions against the real world we can take steps to correct our mistakes. When we cannot, we need to be very careful or we are likely to get it wrong. We need a word to distinguish between the two cases. That word is “empirical”.

Again, if empiricism describes all of human thought, then the term is redundant. All we need is words such as “thought”, “knowledge”, “reason” etc.

Let’s return again to what I think are your main motivations for arguing that everything is empirical.

I think what you really want to say is:

1) There is no sharp dividing line between empirical and a priori knowledge. There are cases which straddle the borderlands between the two (e.g. theoretical physics).

2) All knowledge is at some level derived from the physical universe

I agree with both of those points. I just think you are not expressing them clearly.

I also suspect I would not agree with some of the implications I think you draw from these points. For example, I think you may take (2) as reason to believe that only the physical universe exists, but I would not.

Theology is not unempirical because it is flawed, but because it does not make predictions and revise what beliefs it endorses in light of new evidence.

LikeLike

I’ll say it again – the wrongness of the theory does not imply that the practice is harmful. Look at acupuncture. Totally unscientific theory; practice doesn’t appear to cause harm.

Or – as is likely the case – demonstrating the wrongness of the *theory* is exceedingly difficult due to the vague and obscure nature of the theory and our current state of knowledge regarding the mind, and APA members are either wrong or unsure about the *theory*, and thus look at the practices instead to determine whether they’re harmful or not. Just like EFT/TFT. Just like acupuncture.

You’re presenting a false dichotomy.

Also, expecting Boudry to write what amounts to an entire book refuting Lacan in a blog post is unreasonable. He’s not writing about *why* Lacan is wrong — he’s writing about how we are taken in by the wrongness.

You’re welcome to be unconvinced. I’m equally welcome to be unconvinced by appeals to authority and false dichotomies. If you actually want to defend Freud or Lacan’s actual theories, that’s a discussion I’d love to have.

LikeLike

I just want to add that a lot of your rhetorical techniques (“there’s debate within the field”, “you need to engage deeply with this opaque theory to disprove it”, “this theory has respectability”, “you need to be an expert to say whether this is nonsense”, “here are 250 citations to a bunch of books”) are the some of the most common techniques used to defend pseudosciences.

This is one of the reasons why charity is a bad idea with theories like Lacan’s. In like 10 exchanges, we were not even able to establish that praxis has nothing to do with it. And that’s why I keep urging you to talk about Lacan’s theories themselves rather than side issues about whether the APA is the victim of mass hypnosis or should be sued for malpractice.

LikeLike

This black-and-white approach to the question of psychoanalysis does not seem to me to be right. We have to do nuances.

I find it more useful and informative to compare therapy by talk to therapy by hand manipulation, known as “manual therapy”.

Therapy through talk is a kind of interaction between humans which prolongs the interaction done in touching, grooming, bonding, and manual therapy (including massaging).

All of those physical interactions do have an emotional impact on the participants. The study of those interactions has not produced the equivalents of blind experiments or laboratory research available in other fields.

Here is an article by experienced anthropologist Robin Dunbar, who has also studied the psychological effects of gossip and chatting: “The social role of touch in humans and primates: Behavioural function and neurobiological mechanisms”.

Click to access Dunbar11GroomingBondingHormones.pdf

The quality of manual therapy and psychological manipulation by talk is certainly dependent on the experience, intelligence, and skill of the practitioner, the chiropractor, massager, or psychoanalyst.

There is certainly a lot of knowledge involved, but a knowledge that remains highly personal, is more akin to “praxis” and art, and which cannot be literally translated into rigorous scientific prose in order to communicate all the fine points of this knowledge through articles, textbooks, or school classes.

LikeLike

Hi DM,

Agreed. Indeed the lack of any clear division between these is a central point of what I’m saying.

So we’re basically in agreement.

Possibly not. The points above are the main things (whether to use the word “empirical” being a more minor issue).

I think I can guess where you are heading here! The way I think about “existence” would rule out mathematical platonism, though “existence” is not a concept with an agreed and well-defined meaning, however intuitive it is. (My attempt at that here.)

Well, over history, theology had made loads of predictions, and they had a very bad track record of coming true. At which point the theologians did revise the beliefs, making them no longer make those predictions … and gradually, to be on the safe side, to no longer make any predictions at all, and hence we have today’s apophatic theology.

LikeLike

“I’ll say it again – the wrongness of the theory does not imply that the practice is harmful.”

True. However, there are two things here I’d like to mention. First, it is my understanding that Western medicine is looking at acupuncture to see if there are real underlying phenomena (which we now know there are) referred to by a theory which western medicine does not itself accept. I am unaware of the American Medical Association having Traditional Chinese Medicine as one of its constituent divisions. Second, although psychoanalysis is clearly successful (see the 2009 Harvard Journal of Psychiatry meta-study), there are always patients with whom it does not work, as with any approach. If psychoanalysis is bunk, they have still suffered financial loss in the context of a knowing subterfuge by the profession without any benefit in return. I am no specialist in tort law, but it seems to me that such people would conceivably have a case. If this is not true vis-a-vis the law, then I am clearly mistaken. With acupuncture, things appear to me a bit different, as we can actually identify and explain to the patient the underlying biological mechanisms in terms of endogenous opioids and we believe this to be accurate now as a matter of experimental, verifiable analysis. So if it happens not to work, the financial harm is not connected to any subterfuge regarding the treatment or its approval by medical authorities, but to straightforwardly biological considerations.

I don’t mean to be obtuse, but I fail to see how I am presenting a false dichotomy. The logic of my position follows from Boudry’s view, which seems considerably stronger than yours:

“In saner quarters, however, the French psychiatrist is denounced as an intellectual charlatan: a purveyor of obscure and impenetrable nonsense.”

Boudry’s claim (as is also obvious in the paper he cited) is that psychoanalysis is straightforwardly, obviously pseudoscience. Your claim is very different and much more tempered: “…demonstrating the wrongness of the *theory* is exceedingly difficult due to the vague and obscure nature of the theory and our current state of knowledge regarding the mind….”

You wrote:

“Also, expecting Boudry to write what amounts to an entire book refuting Lacan in a blog post is unreasonable.”

I never asked for a book. When he makes blanket claims about entire subdivisions of psychology and then, when pushed, cites his own work, it is perfectly reasonable in the interest of pursuing the truth to inquire as to the nature of that work and the strength of the arguments.

LikeLike

The logic of the position follows from the strength of Boudry’s claims re: psychoanalysis and its allegedly manifestly false nature as pseudoscience. I am not in a position to adjudicate the matter of Lacanian theory or psychoanalysis. I am simply raising a point about the consequences of making and believing such bold and sweeping pronouncements. In terms of my “rhetorical techniques”- I respectfully disagree and prefer to call it data and circumspection. When one attacks entire subdivisions of established professions, one runs the risk of having one’s claims scrutinized. I don’t think there is anything untoward in this. I kept my analysis of Boudry as brief as possible but felt that, since he had cited his own work when pressed, a reply was germane.

LikeLike

If I could just lengthen the quote from me just a little bit:

The real reason, lets be honest, that textbooks of philosophy arent used is that no one is trusted to write down the core of even “crystal clear” philosophies like Hume’s because there is no perfect agreement on what Hume’s philosophy was…there are many interpretive differences and those differences fill journals…[S]ince there is no [complete] agreement you have to stake out a position of your own and that means digging into the text.

LikeLike

HI Coel,

I am not sure what you don’t get about it.

A definition is not a claim.

An atheist might define God as a necessary being, but an atheist would not claim God is a necessary being because he doesn’t believe there is a God.

LikeLike

Hi Coel,

You will recall that I said that the probability could be different in another possible world. I don’t see how that is a difficult concept, that an entity might be inevitable in one kind of reality, but only possible in another.

LikeLike

Hi DM,

I have already pointed out that I don’t know that metaphysical possibility means or what the word ‘metaphysical’ adds to such a sentence.

I didn’t bring up the word, you did so I am not sure how my inability to define this arbitrarily introduced term is a challenge to the concept of necessary existence.

What you are saying, if I have got your right, is that any mathematical model that I can think of in the abstract, any at all – is a possible concrete world – ie something that could be the totality of existence – just so long as it is logically consistent, yes?

The simplest mathematical model I can think of is a single dimensionless point, that does nothing. Perfectly logically consistent.

So could reality (which by luck is this reality we experience) have been a single dimensionless point and nothing else?

LikeLike

I’m still not sure that I follow. A being that is “inevitable in one kind of reality” is a contingent being, since it is dependent on that type of reality.

Isn’t the whole concept of a “necessary” god one that is “necessary” regardless, and thus necessary in all types of reality?

LikeLike

Having worked with academics for 30 years, I vote for this one.

LikeLike

francisrlb: “God is “not a being but is at once ‘beyond being’ (in the sense that he transcends the totality of existing things) and also absolute “Being itself” (in the sense that he is the source and ground of all things)”.”

This is a very good example of obscurantist’s writing, as by all means that the word ‘being’ is not clearly defined (in addition to the dictionary definition). This will go into the deep of theology, and thus I will not discuss it here now. Furthermore, the following concept must be cleared first.

Yaryaryar: “How can you have a “fundamental theoretical insight” into the conceptual space of being and Being (or whatever) when it quite literally doesn’t exist?”

The word ‘being’ connotes ‘existence’ or a state of existence.

The word ‘nothing’ connotes a state of ‘not a thing is in existence’.

Question: being a concept of representing ‘a state of non-existence’, is ‘nothing’ itself a ‘non-existence’?

In math, the ‘nothing’ is represented as a ‘real’ number, zero (0). Is this real number a non-existence?

Recently, there is a debate about “Why is there something rather than nothing?” It is also the result of the misunderstanding of the meaning of the term ‘nothing’. In mathematics, ‘nothing’ has two forms (R, Y) as below.

R = 0 (non-existence)

Y = 1/0 (infinity)

Then, in Set Theory and Linear Algebra, the R and Y are not as normal as the number 1 and 2 but are the ‘boundaries’ of two ‘closed’ sets.

S = {1, ½, 1/3, …, 1/n, … R} = (1, R)

T = {1, 2, …, n, … Y} = (1, Y)

That is, the both form of ‘nothing’ in math language, they are not ‘non-existence’. Is there a true ‘non-existence’ in ‘this’ universe? This is a good question. My answer is ‘No’ while ‘non-existence’ is a good tool for describing a ‘relative’ existential situation locally. And, I will not go over the details here. I just want to show that your statement is not correct, at least, in one logic universe (the Math.).

LikeLike

Correcting a typo: “… the R and Y are not as normal as the number 1 and 2 but are the ‘boundaries’ of two ‘closed’ sets.”

It should be: “… not only the R and Y are as normal as the number 1 and 2 but are the ‘boundaries’ of two ‘closed’ sets.”

LikeLike

Hi Robin,

I’ve already explained this, surely.

No, you didn’t mention the concept of metaphysical possibility. But it is implicit in the concept of necessity.

Once more:

A necessary being is one that exists in all possible worlds.

A possible world is possible if it is metaphysically possible, because that’s the kind of possibility we are talking about.

We need the term because I maintain that a possible world is just a logically possible world (i.e. that metaphysical possibility is the same as logical possibility) whereas you seem to think this is not the case. We are therefore talking about two different types of possibilities and we need labels to distinguish them.

Or we can approach it from a slightly different angle.

A necessary being is a being which cannot possibly fail to exist. I maintain that this means a necessary being must be logically required (i.e. it’s non-existence is logically impossible) but you maintain that there is some other kind of impossibility apart from logical, and that I am calling metaphysical impossibility (which is actually the accepted term in the literature for what you are talking about).

Yup.

It depends what you mean by reality. Personally, I think reality consists of a multiverse containing all possible worlds. One of those worlds is a single dimensionless mathematical point and nothing else, essentially nothingness.

But yeah, even forgetting the MUH, it does seem to me that it is possible that even if there were only one universe, then that universe could have been nothingness. I see no reason to imagine that only worlds similar to our own could exist, although if they are so very different from our universe we might not want to call them “worlds”, as such.

LikeLike

Hi DM,

Hi Robin,

In my usage, “metaphysical possibility” is just the label for the kind of possibility we are talking about when we discuss possible worlds. I call it that because that is the standard name in the literature, but we could call it “needle-nardle-noo” if you prefer.

It remains incompletely defined because we each have different takes on what possibility means for possible worlds. I think it means logical possibility. You think it means some other kind of possibility. I call this other kind “metaphysical” because that is what it is called by philosophers.

But to attempt to make it more clear, take as a stipulative definition that a proposition is metaphysically possible if there is a possible world where that proposition is true. I then ask you to explain what this kind of possibility means to you in detail, in terms of when it holds and when it does not. If you can’t do that, even in outline, then I think you don’t really have a grasp of what a possible world is to you.

No, that is the distinction between abstract and concrete. The distinction between possible and impossible is different. In the abstract,Mitt Romney might be President of the USA. In the actual, he is not. But there is a possible world where Mitt Romney is the President. There is no possible world where there is a greatest prime number (a logical impossibility).

I would say there is certainly a possible world where there is no God, whereas you seem to be uncertain on this.

I would say the idea of a contingent God is logically possible, but I don’t think it is actual in this particular world.

LikeLike

Hi Coel,

How exactly does that contradict what I am saying?

You appear to have forgotten the point of the exchange.

You said that “necessarily existing” meant “having a probability of 1”

I said they were not equivalent because “necessarily existing” meant existing in all possible worlds, whereas “having a probability of 1” carried no implication of being true in all possible worlds.

So “having a probability of one” only implies that it is, as I said, “inevitable in one kind of reality”.

Whereas “necessarily existing” implies that it exists in any kind of reality.

And so clearly they are not equivalent.

And clearly real theists would not have responded as your imaginary theists did.

LikeLike

Hi Coel,

He does, and you repeat it here when you say:

Implicit in this is the assumption that a designer cannot design anything more complex than itself. If you drop that assumption then invoking a design will reduce the information content as long as the least complex intelligence capable of designing that artifact is less complex than the artifact itself.

Indeed, and if Dawkins had built a more careful argument around this particular premise then he would have had a decent argument against a contingent intelligent being creating the universe.

For all Dawkins undoubted skills in other areas, this is not his forte. People like Graham Oppy, who have taken time to understand the subject matters, make much better arguments.

LikeLike

On the value of reading the original books instead of textbooks versions for undergraduates, here is a quote by Rene Descartes (1596-1650), the French philosopher/mathematician:

“The reading of all good books is indeed like a conversation with the noblest men of past centuries who were the authors of them, nay a carefully studied conversation, in which they reveal to us none but the best of their thoughts.”

This applies to books on science as well as philosophy, in spite of the many opinions to the contrary expressed in this debate.

LikeLike

Human language is dominated by statements about no-things and non-sense – including those about the so called “self” and mind. By definition, there is great demand for it > it sells well. Thus, it prob has little importance and influence on behavior.

LikeLike

I find the discussion about why we study philosophy from original sources interesting, and feel like no-one has given a satisfactory answer (and I don’t really have one, either!). Yes, many have given examples of advantages of reading the ancients, but none of them seem to be absolutely necessary reasons. They all seem to be about developing your abilities, not about actually doing philosophy. Take the analogy about physics demonstrations (I know much less about the importance of personal experience of dissections to biologists): while they are valuable and can be inspiring, you can in principle do theoretical physics just fine without having seen demonstrations and experiments (and a philosopher is much more like a theorist than an experimentalist).

I personally enjoy reading the ‘masters’ in the original, but I cannot say that it’s mostly for epistemic reaons — I really enjoy reading Schopenhauer, and to me reading his prose is like listening to Bach, but that’s an aesthetic reason. I even enjoy reading Kant (though it took some effort at first) — but if someone is interested in knowing what transcendental idealism is and whether it is true or not, I don’t see why it is absolutely crucial to read Kant’s original text. Of course if your goal is to learn what “Kant really meant,” then there’s no other way, because as David Ottlinger points out, it is often the case that people simply don’t agree on what the master ‘really meant.’ But if you are interested in ideas alone, then you can just formulate a dozen different versions that cover all possibilities of what transcendental idealism could reasonably construed to mean, and then evaluate them one by one. It doesn’t matter which one of them was the one Kant himself had in mind. At the end of the day, you (hopefully) have learned something: you have learned new ideas, and you have learned which of them are true and which are false.

In short I don’t see why philosophy by its very nature HAS to be as person-centered/primary literature-centered as it is currently, as a matter of principle. In principle one can perfectly well imagine a kind of philosophizing (which I assume is what e.g. Disagreeable Me is thinking of) where you just lay out the ideas, prove or refute them, and build on them, without the need to refer to specific philosohpers, and at any rate the very first philosopher had to philosophize without the aid of older philosophers to refer to. In fact I think recent academic philosophy has become at least a bit more like this compared to the past. Perhaps the primary-literature method is simply the best in practice; perhaps great philosophers are simply too rare, mediocre philosophers don’t contribute much to the subject compared to mediocre scientists, and maybe mediocre philosophers cannot even be trusted to interpret and explain the master philosophers correctly; but if so no-one has made the case compellingly.

LikeLike

Hi Robin,

I still disagree. He is not making the assumption that in every case where an intelligent designer designs something the result is always less complex. What he is making is the argument (not assumption) that a designer of the capabilities of the

Abrahamic god would be more complex than the things we see around us.

Anyone disagreeing is welcome to write down a simple blueprint of such a god.

LikeLike